The landscape of American education has undergone dramatic transformation over the past century, with school consolidation representing one of the most significant and controversial changes to how communities educate their children. From approximately 200,000 one-room schoolhouses dotting the American countryside in the early 1900s to fewer than 13,500 public school districts today, the merger and consolidation of schools has fundamentally reshaped educational access, community identity, and student experiences across rural and urban America.

School consolidation—the process of merging two or more schools or districts into unified systems—emerged as both practical solution to educational challenges and deeply contested social transformation. While proponents argue consolidated schools provide enhanced educational opportunities, broader course offerings, and improved facilities, critics contend that mergers destroy community identity, increase student travel burdens, and eliminate the personalized attention smaller schools traditionally provided.

Understanding the history of school consolidation reveals complex motivations, unintended consequences, and lasting impacts that continue shaping educational policy debates today. Whether your school district resulted from consolidation decades ago or faces potential merger currently, this comprehensive exploration provides context for appreciating how modern educational institutions evolved and the community heritage they represent.

From the practical origins addressing rural depopulation through waves of efficiency-driven consolidation to contemporary debates about school size and community preservation, the consolidation story encompasses educational philosophy, economic necessity, technological advancement, and cultural values that continue influencing how Americans think about schools and communities.

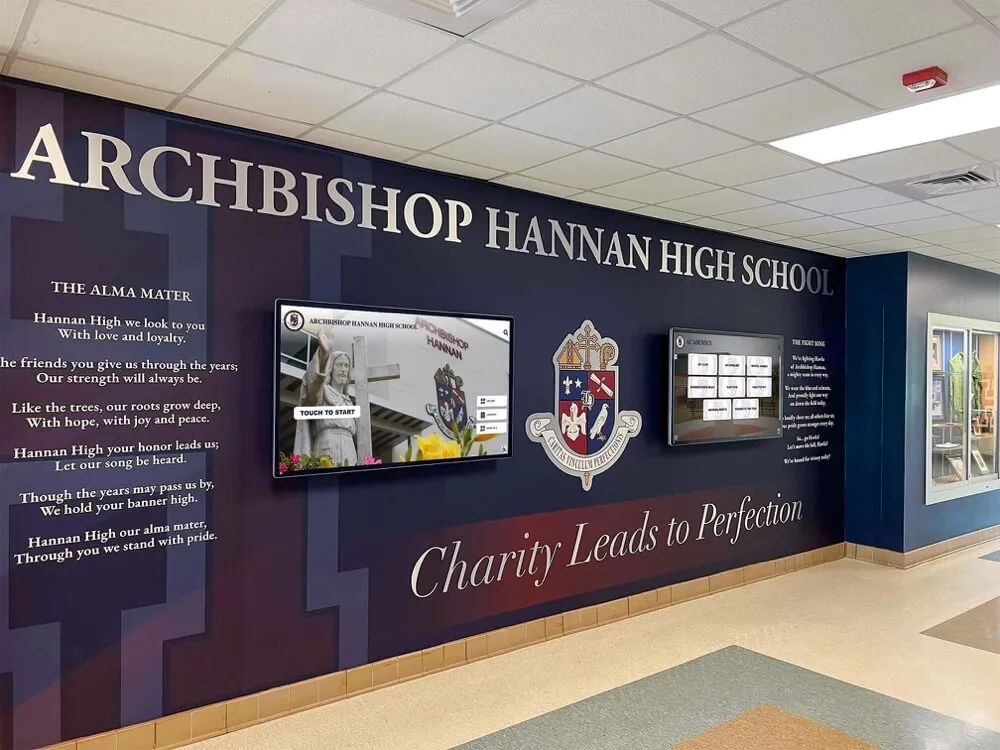

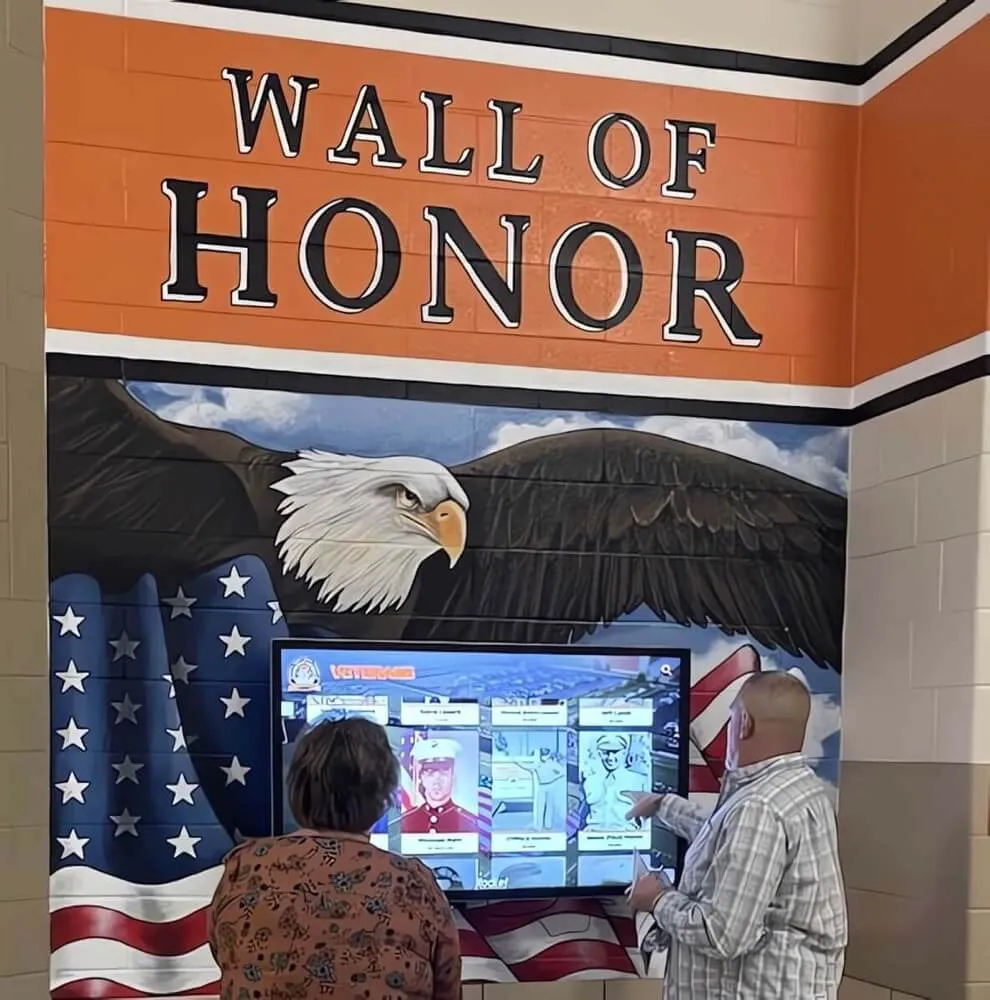

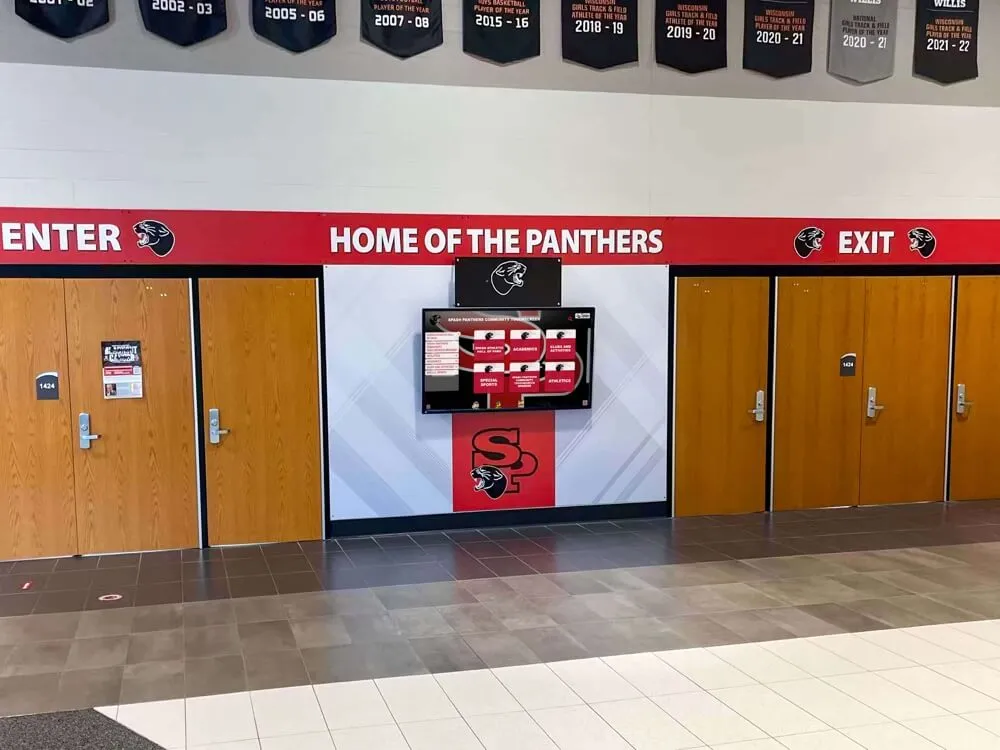

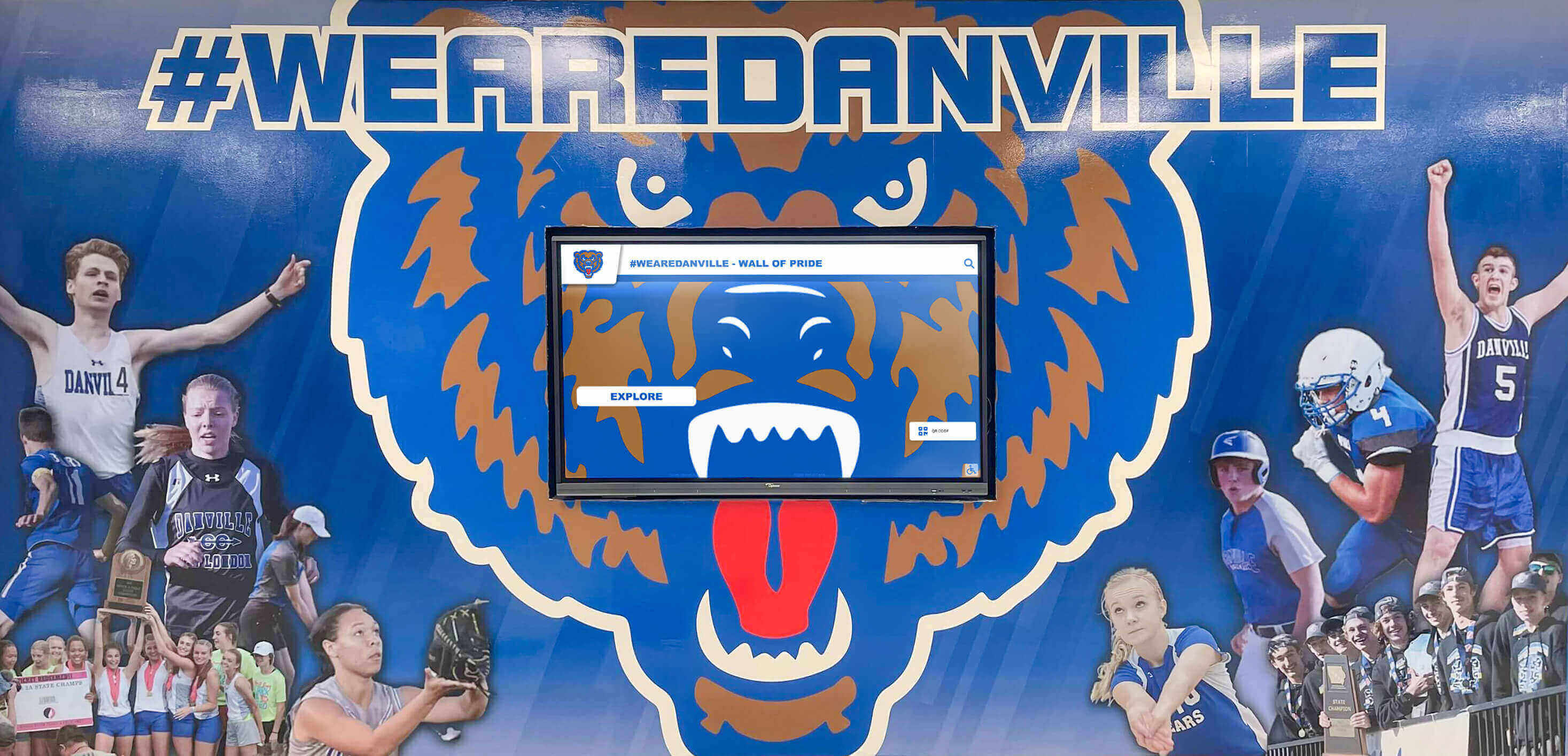

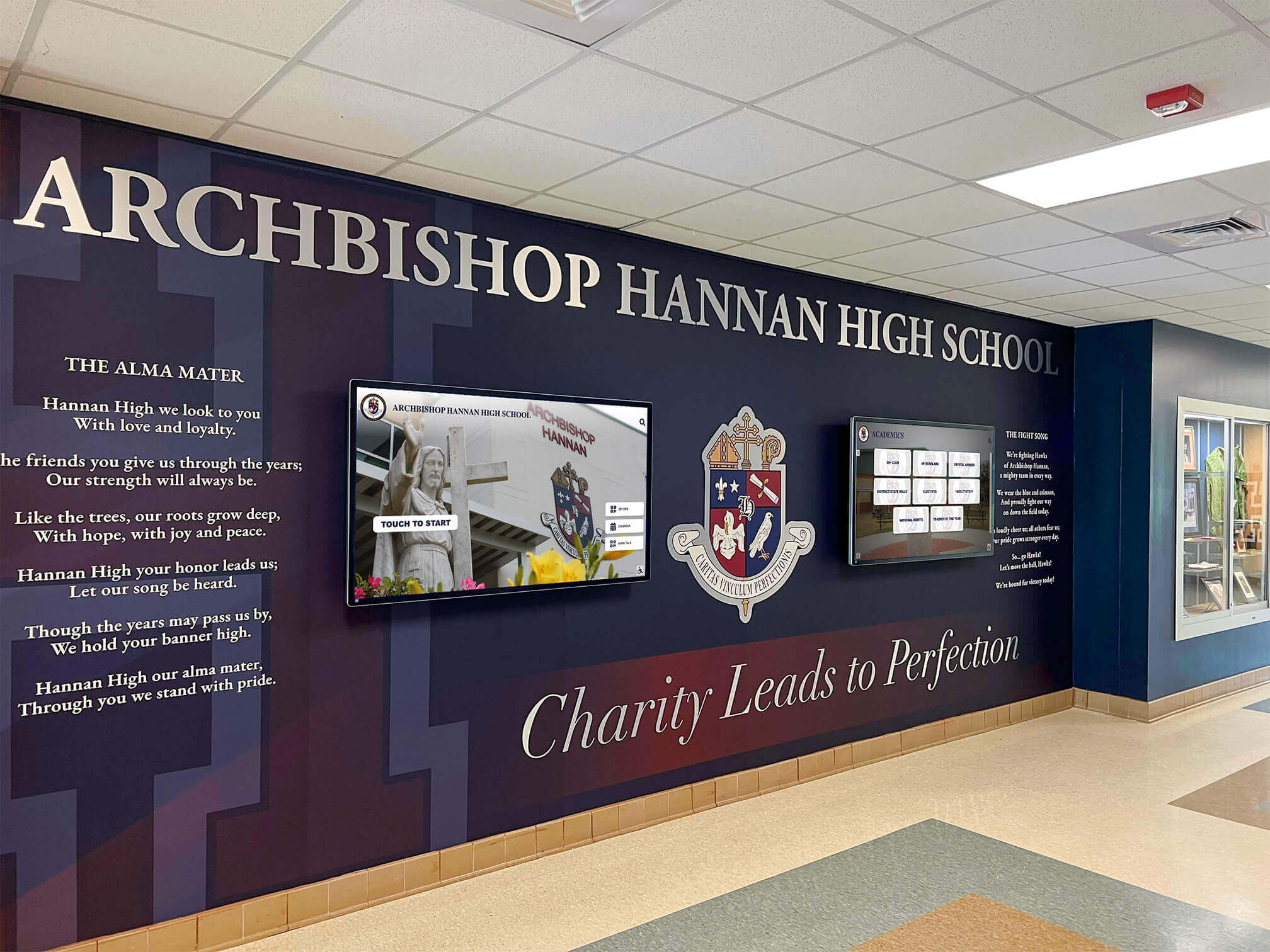

Modern school entrances honor the merged heritage and traditions that consolidation brought together

The Era of One-Room Schoolhouses: Education Before Consolidation

To understand school consolidation’s profound impact, we must first appreciate the educational landscape it transformed. Throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century, American education operated through highly localized, small-scale institutions serving immediate geographic communities.

The Prevalence of One-Room Schools in Rural America

At the turn of the 20th century, approximately 212,000 one-room schoolhouses operated across the United States, serving as the primary educational institutions for rural and small-town America. These schools typically enrolled 10-30 students spanning all elementary grades, taught by a single teacher responsible for instruction across all subjects and age levels.

Geographic necessity drove this decentralized model. Before reliable transportation infrastructure, students needed schools within walking distance—typically less than two miles from home. Rural areas with dispersed populations maintained numerous small schoolhouses ensuring all children could access education without requiring overnight stays or excessive daily travel.

These one-room schools operated under extreme local control. Individual community members often built schoolhouses themselves, hired and paid teachers directly, and determined curriculum based on local values and needs. School terms varied dramatically based on agricultural calendars, with many rural schools operating shortened schedules allowing students to assist with spring planting and fall harvests.

Characteristics and Limitations of Small Rural Schools

The one-room schoolhouse model created intimate educational environments where teachers knew each student personally, older students often assisted younger classmates, and schools functioned as community centers hosting social events, town meetings, and cultural activities beyond formal instruction.

However, significant limitations accompanied these advantages. Single teachers managing multiple grade levels struggled to provide adequate individual attention or grade-appropriate instruction across eight years of schooling simultaneously. Resource constraints meant limited textbooks, scientific equipment, or specialized materials. Teacher qualifications varied enormously—while some possessed formal training, many rural teachers had only elementary education themselves, hired primarily because no more qualified candidates would accept low-paying positions in isolated communities.

Physical conditions often proved challenging. Many one-room schools lacked indoor plumbing, reliable heating, adequate lighting, or proper ventilation. Students of all ages shared single outhouses regardless of weather. Winter attendance suffered when inadequate heating made buildings uncomfortable or families couldn’t spare warm clothing for children to attend safely.

Educational quality varied dramatically based on individual teacher ability, community resources, and local commitment to education. Children in well-funded communities with skilled teachers received solid foundational education, while those in impoverished areas with minimally qualified teachers often learned basic literacy and arithmetic at best.

Modern schools preserve and honor the historical heritage of the smaller institutions they replaced through consolidation

Early Consolidation Movement: 1890s-1920s

The first organized push for school consolidation emerged in the late 19th century, driven by educational reformers, state governments, and progressive advocates who viewed consolidation as essential for modernizing rural education and providing equitable opportunities for all children.

Origins of the Consolidation Philosophy

Several converging factors created momentum for consolidation. The “Country Life Movement” of the early 1900s sought to improve rural living conditions and stem migration to urban areas by enhancing rural institutions, including schools. Leaders argued that better schools would make rural life more attractive while better preparing rural youth for agricultural innovation and rural community leadership.

Educational reformers influenced by emerging progressive philosophy emphasized scientific management, efficiency, and professionalization. They viewed the proliferation of small, locally controlled schools as wasteful, inconsistent, and pedagogically inferior. Consolidation promised economies of scale, professional administration, standardized curriculum, and specialized instruction that small schools could never provide.

State education departments began promoting consolidation actively. State superintendents published studies demonstrating cost efficiencies, quality improvements, and expanded opportunities consolidated schools could deliver. Many states passed legislation encouraging or requiring consolidation through financial incentives, transportation funding, or mandatory minimum enrollment standards.

Transportation Technology Enables Geographic Consolidation

The feasibility of consolidation depended entirely on solving the transportation challenge—how to bring students from dispersed rural areas to centralized locations daily. The development of motorized school buses in the early 20th century made this possible for the first time in history.

The first motorized school buses appeared around 1915, though horse-drawn “school wagons” had transported students to consolidated schools since the 1890s in some areas. Early motorized buses were often makeshift vehicles—farm trucks fitted with benches and canvas covers. Purpose-built school buses with safety features emerged gradually through the 1920s and 1930s.

School transportation represented unprecedented public investment. States that promoted consolidation recognized they must subsidize student transportation for consolidation to succeed politically. Transportation funding became standard component of state education finance formulas, socializing costs that would have fallen on individual families if students traveled to centralized schools independently.

Early Consolidation Examples and Community Resistance

Massachusetts conducted early consolidation experiments in the 1890s, transporting students to town center schools from surrounding rural districts. Ohio, Indiana, and Iowa actively promoted consolidation in the early 1900s through state policies incentivizing districts to merge and providing transportation funding.

However, consolidation encountered fierce community resistance from the beginning. Rural residents viewed local schools as essential community institutions representing local autonomy and identity. The prospect of closing community schools and sending children miles away to unfamiliar institutions sparked passionate opposition.

Common resistance arguments included concerns about student safety during transportation, loss of community control over curriculum and values, elimination of school buildings as community gathering spaces, reduced opportunities for parent involvement with distant schools, fears that consolidated schools would favor town children over rural students, and symbolic loss of community vitality when local schools closed.

Some consolidation efforts failed entirely when communities mobilized effective opposition. Others succeeded only after bitter political battles dividing communities. The pattern of controversial consolidation implementation established during this era would repeat throughout the century.

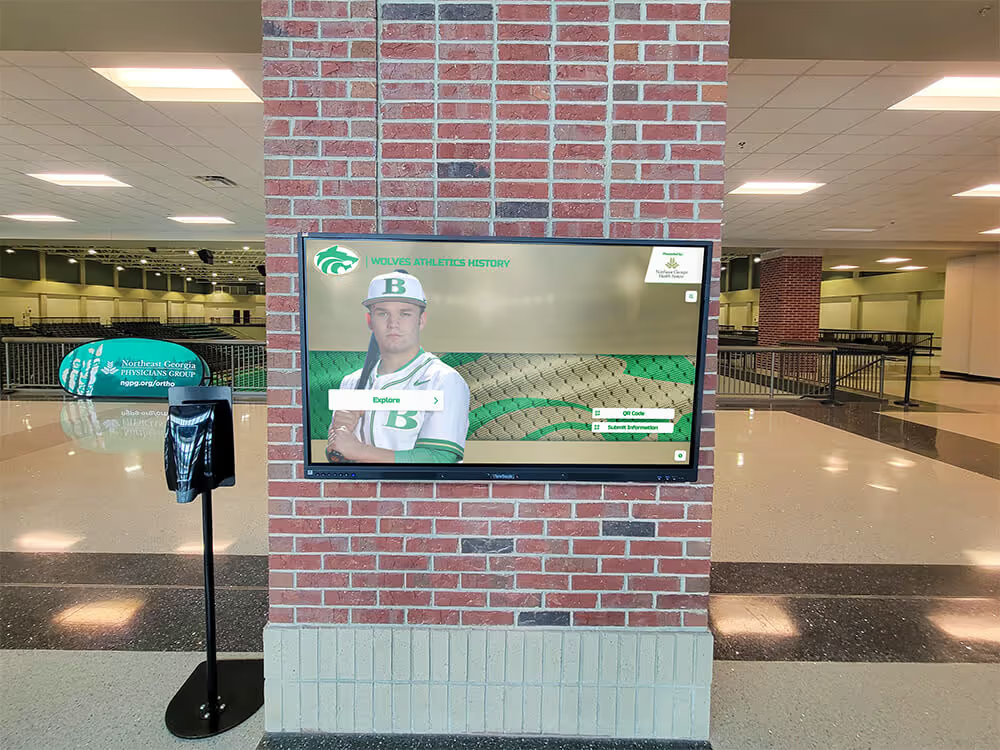

Consolidated schools often serve athletics and activities from multiple former district traditions

The Great Wave of Consolidation: 1930s-1960s

The middle decades of the 20th century witnessed the most dramatic period of school consolidation in American history. During these three decades, the number of public school districts decreased from approximately 127,000 in 1932 to roughly 40,000 by 1960—representing elimination of nearly 70% of existing districts through consolidation and annexation.

Economic Depression and Consolidation Acceleration

The Great Depression of the 1930s paradoxically accelerated consolidation despite economic hardship. Rural areas suffered devastating economic collapse as agricultural prices plummeted. Many small districts could no longer afford to operate schools independently, lacking funds for teacher salaries, building maintenance, or basic supplies.

State governments facing severe fiscal constraints viewed consolidation as financial necessity. Maintaining thousands of small schools required duplicative administrative expenses, facility costs, and staffing that strained state and local budgets. Consolidation promised dramatic cost reductions through eliminating redundant positions, closing underutilized buildings, and achieving economies of scale in purchasing and operations.

Many consolidation advocates framed the policy as educational equity measure. Small, impoverished rural districts provided markedly inferior education compared to well-funded town schools. Consolidation could theoretically equalize opportunities by distributing resources more evenly and ensuring all students accessed qualified teachers and adequate facilities regardless of local community wealth.

Post-War Consolidation and Rural Depopulation

The decades following World War II brought even more dramatic consolidation as rural depopulation accelerated. Mechanization reduced agricultural labor needs, manufacturing jobs concentrated in urban areas, and young people increasingly left rural communities for city opportunities. Rural school enrollments declined precipitously as families departed.

This demographic collapse made many rural schools economically unviable. Districts with dwindling enrollments faced impossible choices—maintain expensive schools serving handfuls of students, significantly raise taxes on remaining residents, or consolidate with neighboring districts spreading fixed costs across larger student populations.

State governments aggressively promoted consolidation during this period through policies requiring minimum district sizes, providing financial incentives for voluntary consolidation, or mandating mergers of small districts. Some states established target district sizes and actively pressured smaller districts to consolidate or face reduced state funding.

The Rural School Consolidation Debate

Educational philosophy clashed with community attachment throughout the consolidation era. Consolidation advocates presented compelling arguments grounded in educational research, efficiency analysis, and professional consensus. They emphasized expanded curriculum offerings consolidated schools could provide—specialized teachers for music, art, physical education, foreign languages, sciences, and mathematics that small schools couldn’t support. Larger schools enabled ability grouping, special education services, and differentiated instruction impossible with 15 students spanning eight grades. Consolidated facilities offered laboratories, libraries, gymnasiums, and equipment small schools could never afford.

Research studies commissioned by state education departments consistently found consolidated schools outperformed one-room schools on standardized assessments and that students from consolidated schools demonstrated better preparation for secondary education and college.

Consolidation opponents countered that quantifiable metrics ignored essential educational and social values small schools provided. They argued that personalized attention, multi-age learning communities, and strong student-teacher relationships created superior environments despite fewer material resources. Small schools fostered community cohesion, gave rural children education close to home without exhausting travel, maintained local control over values and priorities, and symbolized community viability and autonomy.

The debate often became intensely emotional. For many rural residents, school closure represented existential community death. Schools served as community anchors—gathering places, sources of civic pride, and symbols of shared identity. Once schools closed, communities often withered as remaining families departed and businesses relocated.

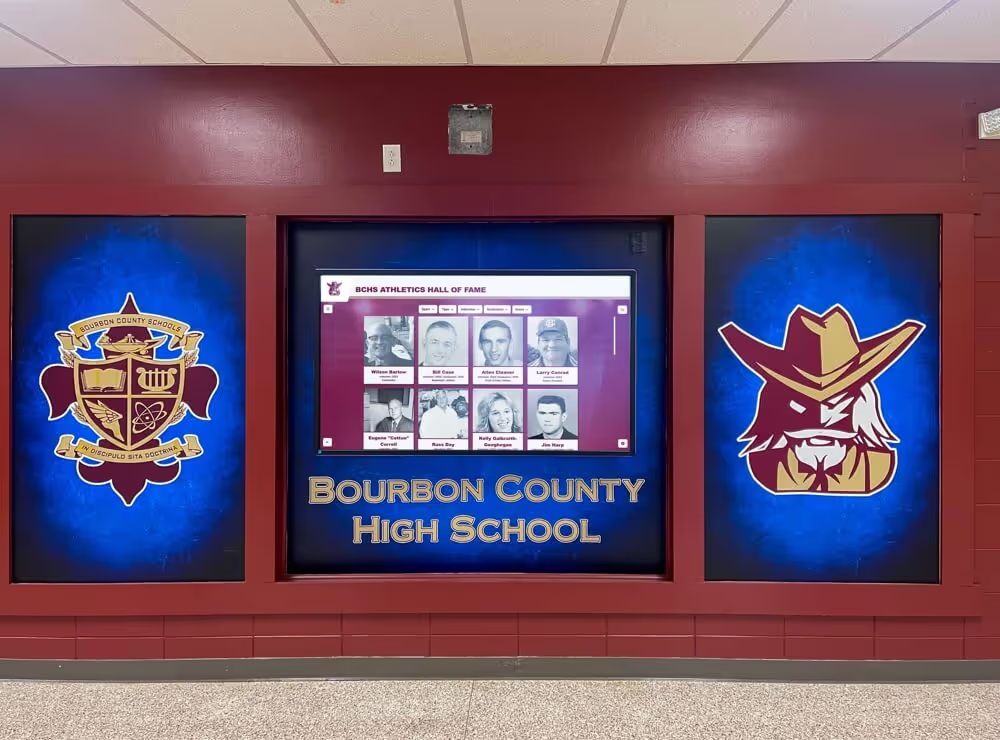

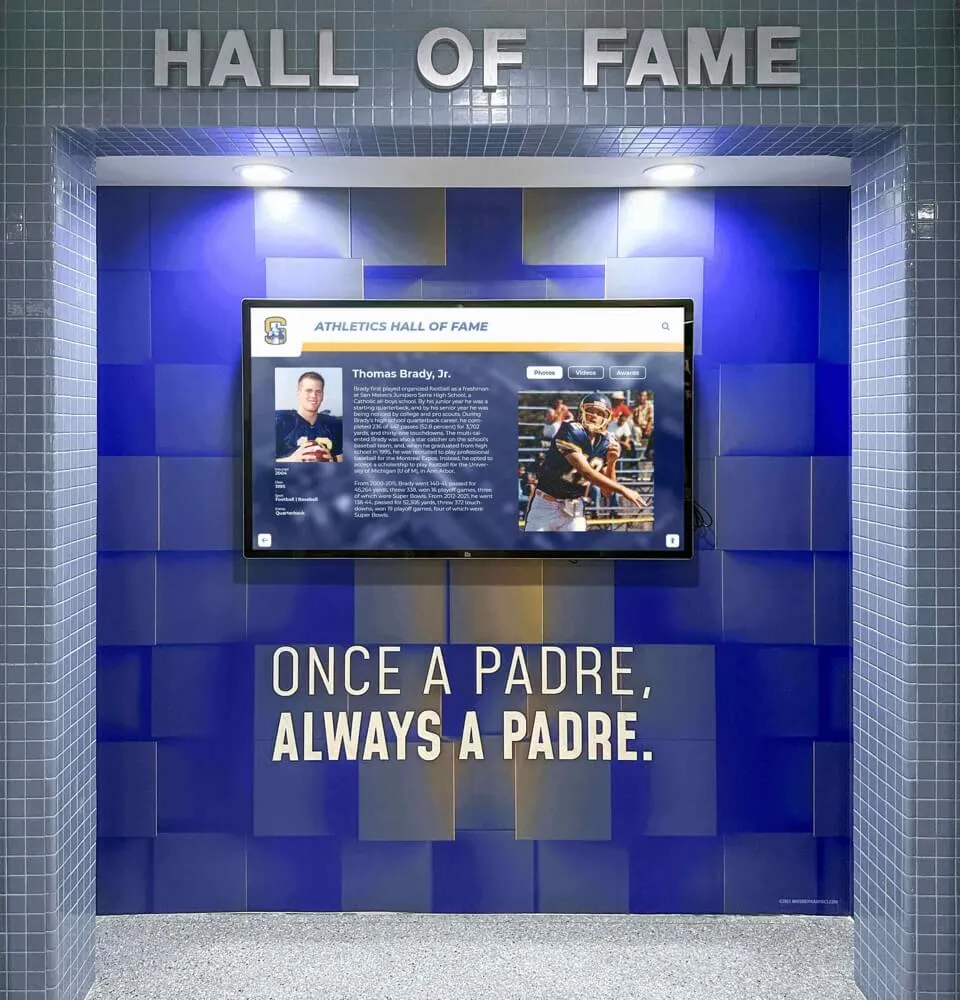

Trophy cases and halls of fame preserve achievement history from schools that merged through consolidation

Methods and Models of School Consolidation

School consolidation occurred through various legal and administrative mechanisms, each creating different structural outcomes and community impacts.

District Consolidation vs. Building Consolidation

Important distinctions exist between consolidating entire school districts versus consolidating individual school buildings within districts. District consolidation merged legally independent governmental units—combining boards of education, administrative structures, tax bases, and all schools into single unified districts. This represented fundamental reorganization of local governance and educational authority.

Building consolidation closed individual schools while maintaining separate district governance. A district might close several elementary buildings and transport all students to fewer, larger schools without merging with other districts. This preserved local control while still centralizing instruction.

These approaches created different political dynamics. District consolidation typically required state legislation or voter approval across affected districts—challenging when communities opposed merger. Building consolidation often fell within existing boards’ authority, requiring only local approval though still generating significant controversy.

Voluntary Consolidation vs. Mandated Merger

Some states encouraged voluntary consolidation through financial incentives—offering construction funding for new consolidated buildings, providing transition funding covering merger costs, or calculating state aid formulas favoring larger districts. This approach respected local autonomy while creating economic motivations for merger consideration.

Other states mandated consolidation through legislation requiring minimum district sizes or enrollments. Districts falling below thresholds faced forced annexation by neighboring districts or state-imposed consolidation. Mandatory approaches generated fierce political resistance but achieved consolidation that voluntary incentives failed to motivate.

Most states employed hybrid strategies—encouraging voluntary consolidation while maintaining authority to mandate mergers when voluntary efforts proved insufficient.

Administrative and Governance Challenges

Consolidating schools created complex administrative challenges beyond simply closing buildings and transporting students. Successfully merged districts needed to reconcile different academic calendars and schedules, integrate diverse curriculum and instructional approaches, merge athletic and activities programs including mascots, team names, and rivalries, combine administrative and support staff from multiple organizations, harmonize salary schedules and benefit structures across formerly independent systems, and balance representation across formerly separate communities in unified governance.

The human dimension often proved most challenging. Principals, teachers, and staff from closed schools sometimes faced demotions, redundancy, or subordination to leadership from rival districts. Athletic programs lost independent identity, with former rivals becoming teammates. Communities lost school board representation as consolidated boards had fewer positions than the sum of previous independent boards.

Many consolidations handled these transitions poorly, creating lasting resentment and dysfunction. Successful consolidations invested significantly in change management—creating transition committees with broad representation, maintaining valued traditions from all predecessor schools, ensuring equitable treatment of staff and communities, and implementing gradual transitions allowing adjustment rather than abrupt transformation.

Interactive displays help consolidated schools honor the complete history and traditions of all predecessor institutions

Regional Variations in Consolidation Patterns

School consolidation unfolded differently across American regions, reflecting distinct demographic patterns, educational traditions, and political cultures.

Midwest and Great Plains: Aggressive Consolidation

The Midwest and Great Plains states experienced the most dramatic consolidation, driven by severe rural depopulation and state policies aggressively promoting consolidation. States like Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota witnessed elimination of thousands of small districts as agricultural mechanization reduced rural populations and state governments mandated minimum district sizes.

These regions maintained particularly dense networks of small schools given dispersed settlement patterns across agricultural land. As populations concentrated, consolidation advocates argued existing school structures became unsustainably inefficient. Many Midwestern states adopted policies essentially forcing small districts to consolidate through financial pressures or explicit mandates.

The result transformed regional educational landscapes. Rural areas that once supported schools every few miles now sent students dozens of miles to consolidated regional schools. Some consolidated districts covered entire counties, with bus rides exceeding an hour each direction for the most distant students.

Southern States: Consolidation and Desegregation

In Southern states, school consolidation intersected with racial desegregation, creating additional complexity and controversy. Many small school districts in the South had been established or maintained to preserve racial segregation—separate districts enabled separate schools for white and Black children.

Federal desegregation orders and state compliance efforts often required district consolidation to eliminate separate systems. However, this overlapped with legitimate economic and demographic pressures for consolidation independent of desegregation. Disentangling racial resistance from genuine community attachment to local schools proved challenging, with opponents of consolidation accused of masking segregationist motives while consolidation advocates sometimes dismissed legitimate community concerns as mere racism.

The timing differed across Southern states based on desegregation implementation. Some consolidated before major desegregation pressure, while others maintained small segregated districts until federal courts mandated integration requiring structural reorganization.

New England: Maintaining Small Districts

New England states consolidated less aggressively than other regions, maintaining comparatively small districts and local control. The tradition of town-based governance and strong local autonomy created political cultures resistant to state-mandated consolidation.

Many New England districts remained quite small by national standards—towns of just a few thousand residents often maintained independent school districts rather than consolidating regionally. When consolidation occurred, it often took the form of voluntary regional districts where multiple towns contracted to operate shared secondary schools while maintaining independent elementary schools.

This regional variation demonstrates how consolidation reflected not just educational philosophy or economic necessity but also deeper political culture regarding appropriate balance between local control and state authority.

Urban and Suburban Contexts

While consolidation discussions typically focus on rural schools, urban areas experienced related processes. Large city school districts emerged through annexing smaller suburban or satellite districts as cities expanded geographically. Suburban consolidation occurred as bedroom communities merged small township districts into larger unified systems serving growing populations.

Urban consolidation raised different issues than rural consolidation—rather than community identity loss, concerns centered on governance efficiency, racial integration, and equitable resource distribution across economically diverse neighborhoods within large districts.

School entrance murals frequently incorporate symbols and colors from all predecessor schools that merged

The Impact of Consolidation on Students and Communities

The effects of school consolidation extended far beyond administrative reorganization or educational delivery, profoundly impacting student experiences, community cohesion, and regional identity in ways that continue resonating decades after specific consolidations occurred.

Effects on Student Educational Experiences

Research examining consolidation’s educational impacts reveals complex, mixed outcomes that defy simplistic assessment. Consolidated schools consistently offered broader curricular options than small schools they replaced. Students gained access to advanced placement courses, foreign language instruction, specialized science and mathematics teachers, comprehensive arts programs, and diverse electives impossible in schools with limited enrollments and teaching staff.

Consolidated schools provided enhanced facilities—modern science laboratories, computer rooms, comprehensive libraries, competitive athletic facilities, and specialized instructional spaces that small school budgets could never support. These material advantages translated into expanded learning opportunities and better preparation for post-secondary education in many measurable dimensions.

However, consolidation costs accompanied these benefits. Larger schools meant students received less individual attention from teachers managing bigger classes and serving more total students. The intimate relationships characteristic of small schools—where teachers knew every student personally and could tailor instruction to individual needs—diminished or disappeared in larger consolidated environments.

Research suggests the relationship between school size and student outcomes forms a curve rather than linear relationship. Moving from very small schools (under 100 students) to moderate size schools (300-600 students) generally improved outcomes by enabling curricular breadth and resource adequacy while maintaining reasonable student-teacher ratios and community feel. However, consolidating into very large schools (over 1,000 students) often produced declining outcomes as institutional anonymity, reduced individual attention, and weakened community eroded the personalization and belongingness that support learning.

Transportation Burdens and Safety Concerns

Consolidation dramatically increased student transportation requirements. Students who previously walked short distances to neighborhood schools now rode buses for 30 minutes, an hour, or even longer in geographically large consolidated districts. For students in the most remote areas of consolidated districts, total commute times sometimes exceeded two hours daily.

These transportation burdens created multiple challenges. Very young children spent significant time confined to buses rather than in educational or play activities. Extracurricular participation became difficult for students dependent on bus transportation when after-school activities required separate transportation arrangements. Homework time decreased, sleep schedules compressed, and family time diminished as transportation consumed hours previously available for other activities.

Safety concerns accompanied increased transportation—more students on roads longer, potential for accidents, children waiting at bus stops in early morning darkness or inclement weather, and teenagers driving themselves long distances to consolidated schools in areas lacking bus service for high school students.

Community Identity and Cohesion

Perhaps consolidation’s most profound and lasting impacts affected community identity and social cohesion. For many small communities, schools represented the primary community institution—the shared space where residents gathered, the accomplishment they collectively took pride in, and the symbol of community vitality and future.

School closure often triggered community decline cascading beyond education itself. Young families considering where to live avoided communities without schools, accelerating depopulation. Local businesses dependent on school employment or student families struggled or closed. Community cohesion weakened when shared institutions disappeared and residents’ lives centered on the distant consolidated town rather than home community.

The process of selecting which community would host consolidated schools created lasting rivalries and resentments. Towns that “won” consolidated schools gained population, business activity, and continued vitality while communities that “lost” often entered terminal decline. These dynamics generated bitter conflicts during consolidation debates as communities fought for survival through securing consolidated schools.

For consolidated districts, creating unified identity proved challenging. Should schools adopt one predecessor’s mascot and colors, disadvantaging others? Create entirely new identity, erasing all previous heritage? Attempt compromises combining elements from all predecessors? Different approaches each created issues—continued loyalty to predecessor schools, resentment of “losing” identity, or awkward combinations satisfying no one.

Many consolidated schools struggled for years or decades to forge cohesive identity and community support as residents maintained loyalty to closed predecessor schools rather than embracing consolidated replacements.

Murals and digital displays help consolidated schools celebrate the complete athletic heritage from all predecessor institutions

Preserving Heritage in Consolidated School Districts

Successfully consolidated districts learned that acknowledging and honoring predecessor school heritage proved essential for building unified identity and community support. Ignoring or erasing previous school traditions created lasting resentment, while thoughtfully preserving heritage helped communities embrace consolidated institutions as legitimate successors to valued predecessors.

Challenges of Balancing Multiple School Histories

When three, four, or more schools merged, preserving all predecessor traditions comprehensively proved practically difficult. Athletic trophy cases, hall of fame displays, and historical exhibits occupy limited physical space. Attempting to include all predecessors equally often resulted in superficial treatment satisfying no one, while emphasizing some over others generated accusations of favoritism and disrespect.

Traditional static displays faced inherent capacity constraints. A trophy case might display 50-100 accomplishments total—inadequate for comprehensively representing multiple predecessor schools each with decades of history. Selections inevitably felt incomplete or unfair, with some eras, sports, or communities better represented than others based on arbitrary spatial limitations.

Mascot and color decisions proved particularly contentious. Adopting one predecessor’s identity meant others “lost” theirs. Creating entirely new mascots and colors erased all previous identities. Combination approaches—like using multiple colors or hyphenated mascot names—often felt forced and satisfied no constituency fully.

Traditional Approaches to Heritage Preservation

Many consolidated schools attempted heritage preservation through traditional methods including naming buildings after closed schools, creating memorial plaques acknowledging predecessor institutions, maintaining some closed school buildings as museums or community centers, displaying merged trophies and photos in available spaces, and organizing alumni reunions acknowledging separate predecessor school identities.

These approaches provided some recognition but struggled with inherent limitations. Named buildings honored institutions but didn’t actively engage students or visitors with actual heritage and accomplishments. Plaques acknowledged existence but conveyed little substantive history. Museums in closed buildings served nostalgia for former students but didn’t integrate heritage into daily life of consolidated schools.

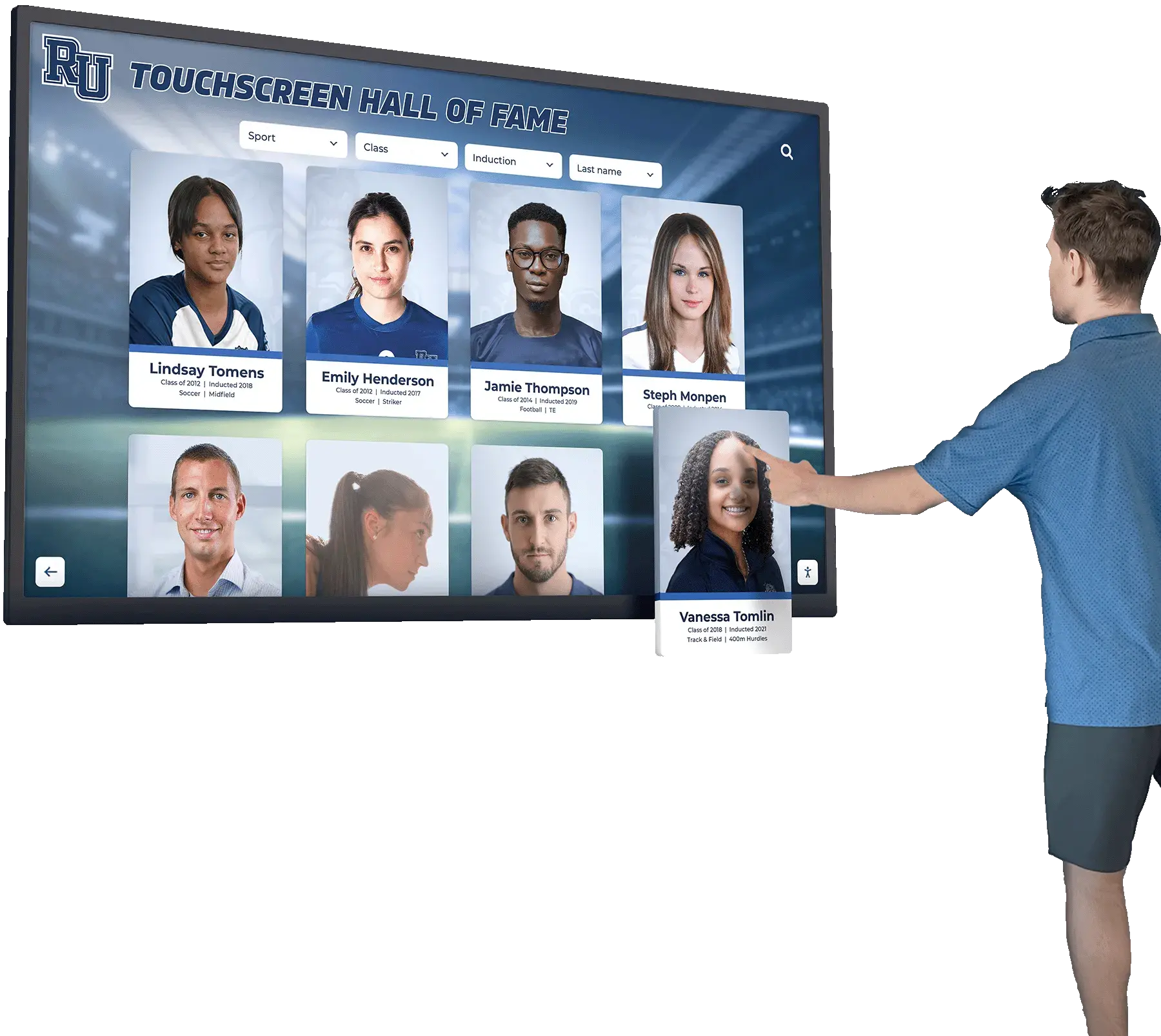

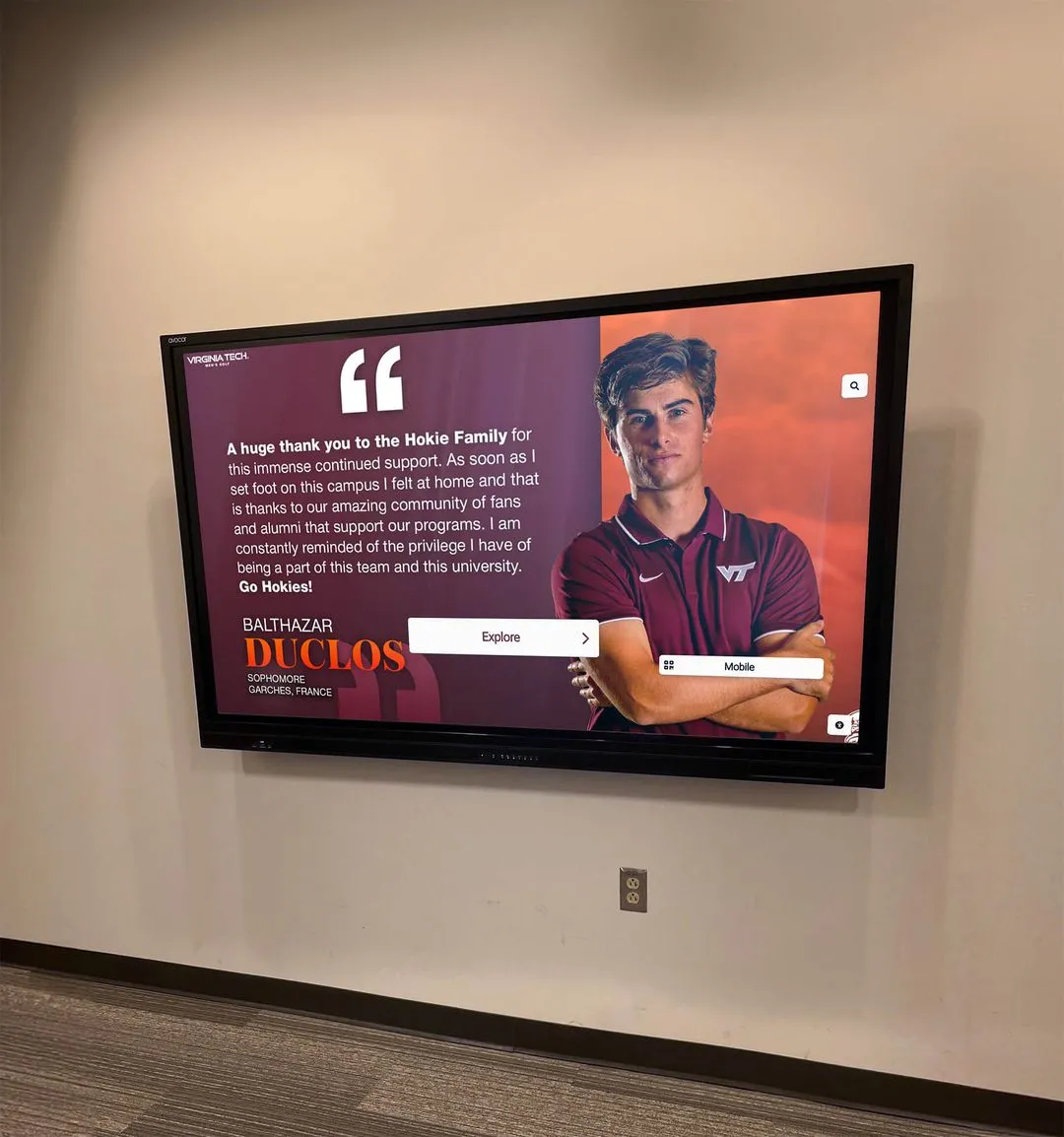

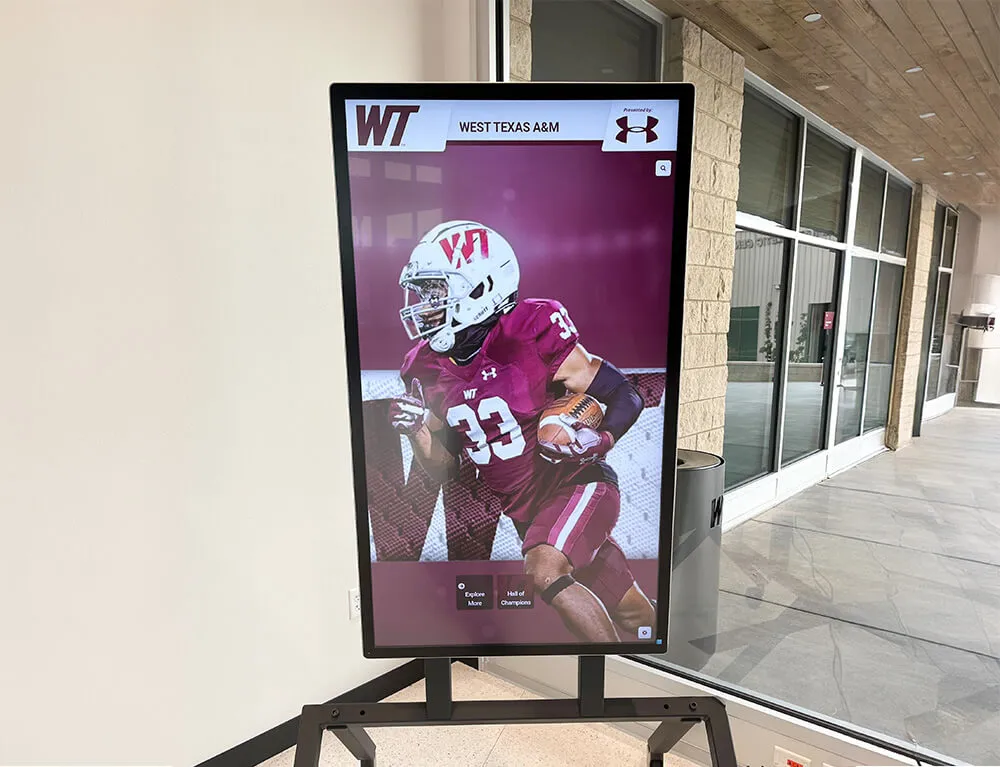

Digital Recognition Solutions for Comprehensive Heritage Preservation

Modern digital recognition displays provide transformational solutions for consolidated schools struggling to honor complete heritage from multiple predecessor institutions. Unlike physical displays constrained by limited space, digital systems accommodate unlimited content—enabling comprehensive representation of all schools, all eras, and all forms of achievement without forced selection or exclusion.

Solutions like Rocket Alumni Solutions enable consolidated districts to create searchable databases including athletes, scholars, and distinguished individuals from all predecessor schools throughout history. Students and community members can explore complete athletic records, academic achievements, and alumni accomplishments across all schools that merged, discovering their school’s full heritage through intuitive interfaces.

Interactive touchscreen displays become gathering points where alumni from different predecessor schools can search for their own achievements and reconnect with classmates, current students can discover role models and traditions from their district’s complete history, and families can understand the rich heritage their consolidated district inherited from multiple contributing communities.

Web accessibility extends heritage preservation beyond physical campus. Alumni living anywhere globally can access their school’s history, submit updated profile information, and maintain connection to educational communities—whether those communities operate independently today or merged into consolidated districts decades ago.

This comprehensive approach helps consolidated districts honor all predecessor traditions equitably while building unified identity that acknowledges rather than erases the multiple streams of heritage contributing to present institutions.

Digital touchscreen systems allow unlimited achievement recognition from all predecessor schools without physical space constraints

Contemporary School Consolidation Debates

While the massive consolidation wave of the mid-20th century ended, consolidation remains active in many regions today, particularly in areas experiencing continued rural depopulation or facing severe fiscal constraints. Contemporary consolidation debates echo historical arguments while incorporating new considerations around educational philosophy, technology, and community sustainability.

Ongoing Consolidation in Rural America

Many rural areas continue experiencing population decline as young people depart for urban opportunities, agricultural operations require fewer workers, and small towns struggle economically. School enrollments in these communities have declined precipitously—districts once serving hundreds of students now educate dozens, making independent operation increasingly difficult to justify or finance.

State governments continue promoting consolidation in these contexts through similar mechanisms used historically—minimum enrollment requirements, financial incentives for voluntary consolidation, and state aid formulas favoring larger districts. However, remaining small districts often resist fiercely, representing communities’ last remaining public institutions and final symbols of community viability.

Contemporary rural consolidation generates the same passionate debates seen historically. Proponents emphasize fiscal responsibility given declining enrollments, improved educational opportunities through broader course offerings and better facilities, and enhanced competitiveness for students accessing more comprehensive programs. Opponents stress community identity destruction, excessive student transportation burdens, loss of personalized educational environments, and the symbolic death small town school closures represent.

School Size Research and Optimal Enrollment Debates

Educational research has increasingly questioned assumptions underlying historical consolidation advocacy—particularly the belief that larger schools inherently deliver superior education. Substantial research now suggests moderate-sized schools (400-800 students for high schools, 300-500 for elementary schools) often produce better outcomes than either very small or very large schools.

This research emphasizes that school culture, community engagement, and student belongingness significantly influence educational outcomes—factors often stronger in smaller schools despite fewer material resources. Students in smaller schools report greater engagement, stronger relationships with teachers, more participation in activities, and higher sense of connection to their schools.

These findings have informed more nuanced approaches to consolidation in some states. Rather than assuming “bigger is better,” contemporary policy increasingly recognizes optimal size ranges balancing curricular breadth, resource efficiency, and community scale that supports engagement and belongingness.

Financial Pressures and Consolidation Realities

Despite research questioning unlimited growth benefits, fiscal realities continue driving consolidation consideration. Districts with declining enrollments face harsh mathematics—fixed costs for buildings, transportation, administration, and base staffing don’t decline proportionally with enrollment. As student populations decrease, per-pupil costs increase dramatically, often requiring service cuts, significant tax increases, or consolidation to maintain educational quality within available resources.

State funding formulas often make small district operation financially challenging. Many funding mechanisms include enrollment-driven components meaning smaller districts receive proportionally less despite facing similar fixed costs as larger districts. Some states have implemented “small school” funding adjustments to partially offset these challenges, but fiscal pressures remain severe in many regions.

Technology and Distance Learning Alternatives

Some contemporary districts have explored alternatives to physical consolidation through technology-enabled distance learning. Rural schools might maintain separate buildings while sharing specialized teachers through videoconferencing, enabling advanced courses that single schools couldn’t support independently. Students in small schools can access foreign languages, advanced mathematics, specialized sciences, or other courses taught remotely by instructors serving multiple small schools.

These approaches preserve community schools and avoid transportation burdens while providing curricular breadth that historically required consolidation. However, distance learning creates its own challenges—technology infrastructure requirements, quality differences from in-person instruction, reduced student engagement in remote formats, and limitations of virtual interaction for certain subjects.

Distance learning has gained prominence following pandemic-driven remote instruction, but remains controversial regarding long-term viability as full consolidation alternative versus supplemental approach addressing specific limitations.

Modern schools preserve complete achievement records from predecessor institutions through comprehensive recognition systems

Case Studies: Successful and Problematic Consolidations

Examining specific consolidation experiences reveals factors distinguishing successful consolidations that built thriving unified districts from problematic mergers that created lasting dysfunction and community division.

Example: Thoughtful Consolidation with Heritage Preservation

One Midwestern consolidated district formed by merging three small rural high schools in the 1990s exemplifies successful consolidation practices. District leadership established a broad transition committee including representatives from all three predecessor schools, conducted extensive community engagement soliciting input on new school identity, and made deliberate choices preserving valued traditions.

The consolidated school adopted entirely new mascot and colors rather than selecting one predecessor’s identity, designing symbols incorporating elements from all three schools. Athletic teams competed in “memorial” tournaments honoring each predecessor school’s name and tradition. The new school building featured dedicated sections celebrating each predecessor’s history, with trophy displays, photo walls, and historical exhibits providing equitable representation.

Most significantly, district leadership emphasized including alumni from all predecessor schools in consolidated school community. Annual all-alumni events welcomed graduates from all schools, communications consistently acknowledged the district’s multiple heritage streams, and recognition programs honored distinguished alumni from each predecessor equally.

Enrollment in the consolidated school remained stable despite many families initially opposing consolidation. The thoughtful transition process, equitable heritage preservation, and genuine community building gradually converted skeptics. Surveys conducted five years post-consolidation showed majority approval even among those who initially opposed the merger—a remarkable outcome given consolidation’s typically divisive nature.

Example: Poorly Executed Consolidation Creating Lasting Division

A contrasting example from a Southern state illustrates how poor consolidation processes create lasting problems. State mandate forced merger of three small districts over strong local opposition. State officials selected the consolidated school location without meaningful community input, choosing the largest predecessor town despite geographic centrality that would have reduced transportation burdens if built mid-way between communities.

The consolidated school adopted the largest predecessor’s mascot, colors, and name—essentially treating consolidation as the other two schools being absorbed rather than equal partners creating new unified identity. Staff from closed schools received lower priority for positions in consolidated district, generating resentment. Community members from “losing” schools perceived and received treatment as second-class citizens in the new system.

Predictable results followed. Residents from closed school communities actively opposed consolidated district initiatives including bond referendums for facilities improvements that repeatedly failed despite obvious need. Athletic programs struggled as community members continued identifying with closed predecessor schools rather than supporting consolidated teams. Board meetings regularly devolved into conflicts along old school lines rather than unified governance serving all students.

Twenty years after consolidation, underlying divisions remain visible. The geographic location chosen generated transportation burdens creating lasting resentment. The decision to essentially erase two schools’ identities while preserving the third created justified perception of disrespect. The lack of genuine transition process or community building meant the district never truly consolidated psychologically despite legal and administrative merger.

Lessons from Consolidation Experiences

Successful consolidations share common characteristics including extensive transition planning with broad community representation, equitable treatment of all predecessor schools rather than “winner” and “loser” dynamics, thoughtful new identity creation or balanced heritage preservation when maintaining elements from predecessors, genuine community engagement during and after transition, and continued acknowledgment of multiple heritage streams rather than attempting to erase predecessor school memories.

Problematic consolidations typically feature top-down mandates without community engagement, geographic or identity choices favoring one community over others, inadequate attention to symbolism and heritage preservation, treating consolidation as administrative process rather than community transformation, and assumptions that unified identity will develop automatically without intentional cultivation.

These patterns reveal that consolidation success depends less on whether consolidation occurs than on how transition processes respect community attachment to schools while building genuine unified identity honoring all contributing traditions.

Successful consolidated schools integrate symbols, crests, and heritage from all predecessor institutions in unified displays

The Continuing Legacy of School Consolidation

The consolidation era transformed American education permanently, creating the district structures and school sizes that characterize contemporary education. Understanding this history provides context for appreciating how your school or district evolved and recognizing the heritage it represents.

Statistical Overview of Consolidation’s Impact

The numbers tell a dramatic story. In 1932, the United States had approximately 127,000 public school districts. By 2025, that number declined to fewer than 13,500—a reduction of more than 90%. The number of public schools decreased from roughly 271,000 in 1930 to approximately 98,000 today despite the total U.S. population more than tripling during the same period.

Average school size increased correspondingly. The typical school in 1930 enrolled fewer than 100 students; today’s average elementary school serves over 500 students, while typical high schools enroll 700-800 students with many urban and suburban schools exceeding 2,000-3,000 students.

These statistics represent millions of individual and community experiences—students who transitioned from small known schools to large consolidated institutions, teachers who lost positions or adapted to dramatically different environments, communities that lost their schools and often their vitality, and families that experienced both benefits and costs of consolidation firsthand.

Modern School Districts as Products of Consolidation History

Most current school districts represent consolidation results rather than original configurations. If your district serves an entire county, chances are it resulted from consolidating dozens of smaller districts. If your school name includes directional identifiers (“Central,” “North,” “Regional”) or references multiple communities (“Tri-Valley,” “Twin Rivers”), consolidation likely created it.

Many contemporary debates about school size, district organization, and community attachment echo historical consolidation controversies. Arguments about optimal school size, value of neighborhood schools, importance of walkable communities, and balance between efficiency and community continue consolidation-era discussions in new contexts.

Understanding this history helps contextualize current decisions. Whether your district considers further consolidation, debates closing neighborhood schools in favor of larger facilities, or discusses preserving small schools despite economic pressures, you’re participating in debates with century-long history and complex legacy.

Honoring Complete Heritage in Consolidated Districts

For districts that resulted from consolidation, thoughtfully preserving complete heritage from all predecessor schools helps build unified identity while respecting community attachment to previous institutions. This involves actively acknowledging multiple heritage streams rather than treating one predecessor as primary while others are secondary or forgotten.

Alumni recognition programs can include distinguished graduates from all predecessor schools. Historical exhibits can represent all schools equitably. Athletic record displays can showcase championships from each institution. School histories can acknowledge all contributing traditions rather than treating consolidated school as entirely new entity without predecessor connection.

Digital recognition systems provide particularly effective tools for comprehensive heritage preservation in consolidated districts. Interactive displays can accommodate unlimited content from all predecessor schools, enabling current students to explore their district’s full history while alumni from closed schools maintain connection to their educational heritage.

Athletic facilities in consolidated schools showcase championships and achievements from all predecessor institutions

Practical Considerations for Districts Facing Consolidation Today

While massive mid-20th century consolidation waves have ended, many districts continue facing consolidation decisions due to enrollment decline, fiscal pressure, or state mandates. Drawing on historical experience and research can inform more thoughtful consolidation processes that maximize benefits while respecting legitimate community concerns.

Conducting Thoughtful Consolidation Feasibility Studies

Districts seriously considering consolidation should conduct comprehensive feasibility studies examining financial implications including projected savings from consolidation versus transition costs and ongoing expenses, educational impact assessing curriculum breadth, student services, facility quality, and instructional staffing, transportation requirements calculating routes, times, costs, and safety considerations, and community effects evaluating social cohesion, identity impacts, and community sustainability.

These studies should include genuine community engagement rather than presenting consolidation as predetermined conclusion requiring rubber-stamp approval. Understanding community concerns, addressing legitimate objections, and building consensus around decisions significantly increases consolidation success when it proceeds.

Alternative Approaches to Consider

Before consolidating, districts should explore alternatives that might address underlying concerns while preserving independent operation. Options include cooperative service agreements where districts share specialized teachers, administrative services, or facilities while maintaining separate schools, partial consolidation maintaining independent elementary schools while sharing secondary education, facility upgrades modernizing existing buildings rather than consolidating into new construction, and operational efficiencies improving purchasing, energy usage, and administrative processes to reduce costs without consolidation.

Technology-enabled resource sharing through distance learning or hybrid instruction can provide curricular breadth historically requiring consolidation. While not perfect substitutes for comprehensive in-person programs, these approaches might offer middle ground preserving community schools while addressing educational program limitations.

If Consolidation Proceeds: Best Practices for Success

When consolidation proves necessary or inevitable, specific practices improve outcomes and reduce community division.

Inclusive Transition Planning: Establish transition committees including representatives from all affected districts—board members, administrators, teachers, parents, students, and community members. Ensure all constituencies receive genuine voice in transition decisions rather than token consultation on predetermined plans.

Equitable Heritage Treatment: Make deliberate choices respecting all predecessor schools equally. If adopting new mascot and colors, explain rationale clearly. If maintaining one predecessor’s identity, acknowledge this explicitly while establishing specific ways other schools’ heritage will be preserved and honored.

Strategic Communication: Maintain transparent, frequent communication throughout transition. Address concerns directly, provide accurate information countering misinformation, and celebrate positive milestones in consolidation process.

Comprehensive Heritage Preservation: Implement recognition systems preserving achievements, traditions, and history from all predecessor schools. Ensure athletes, scholars, and distinguished alumni from all schools receive equal recognition in consolidated displays.

Staff Integration: Treat faculty and staff from all predecessor schools equitably during integration. Avoid perception that employees from one school receive preferential treatment while others face disadvantage.

Community Building: Organize events bringing together communities from all predecessor schools in positive contexts. Alumni gatherings, commemorative ceremonies, and tradition-sharing celebrations help build unified identity while honoring separate histories.

Long-Term Identity Development: Recognize that unified identity develops gradually rather than immediately. Continue acknowledging multiple heritage streams for years or decades post-consolidation rather than expecting instant unified culture.

Display walls combining traditional shields with digital screens honor heritage while enabling unlimited recognition capacity

The Role of Community Identity in Educational Success

The school consolidation story ultimately concerns community identity as much as educational administration. Schools represent far more than instructional delivery systems—they embody community values, preserve collective memory, and symbolize shared identity across generations.

Schools as Community Anchors

Particularly in smaller communities, schools function as primary community institutions. They provide gathering spaces for events beyond education—youth sports, civic meetings, cultural performances, and social celebrations. School events create shared experiences connecting community members. Athletic teams generate communal pride and identity. School histories preserve community stories and accomplish achievements.

When schools close, communities often lose their central organizing institution. Residents’ lives increasingly center on the distant consolidated town where children attend school rather than home communities. Shared identity weakens when common institutions disappear. Young families avoid communities without schools, accelerating population decline and economic erosion.

This explains why school closure generates passionate opposition incommensurate with purely educational considerations. Residents understand instinctively that losing schools threatens community survival beyond just education logistics.

Balancing Educational and Community Values

The tension between educational efficiency and community preservation creates policy dilemmas without perfect solutions. Very small schools struggling to provide adequate curriculum or afford qualified teachers in all subjects present legitimate educational concerns. However, forcing consolidation ignoring community attachment and identity creates social costs alongside educational benefits.

More nuanced approaches recognize that “optimal” school sizes balance multiple considerations—educational program quality, fiscal efficiency, community scale supporting engagement and belongingness, and transportation practicality. This suggests avoiding both extremely small schools unable to provide adequate programs and extremely large institutions where students become anonymous within impersonal bureaucracies.

It also suggests that consolidation decisions should incorporate community impact assessment alongside educational and fiscal analysis. What seems efficient administratively may produce community costs—population decline, economic erosion, weakened social cohesion—that outweigh educational benefits, particularly when consolidation eliminates not just schools but community viability.

The Importance of Heritage Preservation Post-Consolidation

For communities that experienced consolidation, thoughtful heritage preservation serves multiple valuable purposes. It demonstrates respect for community attachment to closed schools, validates that predecessor institutions and their accomplishments retain significance, provides concrete connection between past and present enabling community members to see continuity rather than erasure, and helps build unified identity in consolidated districts by acknowledging rather than denying multiple heritage streams.

Digital recognition walls and comprehensive achievement displays serve these purposes effectively by accommodating unlimited content from all predecessor schools, enabling searchable exploration of complete district history, providing both physical displays for on-campus engagement and web access for distant alumni, and creating natural gathering points where alumni can reconnect with school heritage.

This investment in heritage preservation strengthens consolidated districts by building broader community support, maintaining engagement of alumni from all predecessor schools, demonstrating respect for community identity and tradition, and helping current students understand their district’s complete history and the multiple communities it serves.

Interactive kiosks in consolidated school lobbies enable visitors to explore complete heritage from all predecessor institutions

Looking Forward: The Future of School Size and Organization

As we move deeper into the 21st century, ongoing debates about school size, district organization, and community education suggest consolidation remains active rather than purely historical topic.

Demographic Trends and Future Consolidation Pressure

Birth rate decline, continued rural depopulation, and shifting settlement patterns suggest ongoing consolidation pressure in many regions. Rural school districts continue experiencing enrollment decline as young people depart for urban opportunities and remaining populations age. Some projections estimate that thousands of small rural districts will face closure or forced consolidation within the next few decades absent significant policy changes.

Simultaneously, some areas experiencing rapid growth face opposite challenges—expanding enrollments requiring new schools rather than consolidation. Suburban growth zones, exurban development areas, and select cities seeing population gains need educational capacity expansion.

This creates national paradox—rural consolidation continuing alongside urban/suburban expansion producing dramatically different educational landscapes across regions.

Alternative Education Models and Virtual Schools

Technology development has enabled alternative education models that complicate traditional consolidation considerations. Virtual schools serving students remotely regardless of geographic location, hybrid models combining limited in-person attendance with online instruction, micro-schools serving small student cohorts through innovative approaches, and educational cooperatives sharing resources across multiple small schools all provide alternatives to traditional consolidation.

Whether these models ultimately prove educationally and operationally viable at scale remains uncertain. Early evidence suggests that virtual education works well for some students and subjects but poorly for others, particularly younger children, students with special needs, and subjects requiring hands-on activities. Alternative models likely complement rather than replace traditional schools, but may provide options reducing consolidation pressure in some contexts.

Renewed Appreciation for Community-Scale Education

Paradoxically, as massive consolidation continues in some regions, other areas show renewed appreciation for community-scale education. Some consolidated districts have actually deconsolidated—splitting into smaller units better serving distinct communities. Educational research emphasizing school culture, student belongingness, and community engagement has validated values small schools traditionally provided.

“Small schools movement” advocates have established numerous small schools within large urban districts, demonstrating that deliberate community creation can occur even within large systems. These reforms acknowledge that school size matters for student experience and educational outcomes—not just for operational efficiency.

Policy Approaches Supporting Small Schools

Some states have implemented policies supporting small school viability as alternative to mandated consolidation. Approaches include adjusted funding formulas providing per-pupil amounts recognizing fixed costs facing small districts, distance learning infrastructure enabling resource sharing without physical consolidation, strategic investment in rural community development reducing population decline driving consolidation pressure, and flexible staffing models supporting small schools through shared teachers, combined positions, and alternative licensure.

These policies reflect recognition that consolidation creates genuine costs alongside benefits, and that supporting small school viability where communities strongly prefer it may be legitimate policy choice rather than forcing consolidation despite community opposition.

Cafeteria and common space murals in consolidated schools celebrate traditions and symbols from all predecessor schools

Conclusion: Understanding Consolidation’s Complex Legacy

The history of consolidated schools reveals that simple narratives—whether celebrating consolidation as pure progress or condemning it as community destruction—miss the complex reality. School consolidation simultaneously represented pragmatic response to demographic and economic changes, delivered genuine educational improvements for many students, destroyed valued community institutions and identities, and created lasting impacts shaping contemporary education and communities.

Understanding this nuanced history helps contemporary educators, administrators, policymakers, and community members appreciate the districts and schools serving students today. Most existing districts resulted from consolidation processes, incorporating heritage from multiple predecessor schools with their own traditions, achievements, and community connections. Thoughtfully preserving and honoring this complete history strengthens current institutions while respecting the communities they serve.

For districts formed through consolidation, heritage preservation serves as ongoing responsibility rather than one-time transition task. Each generation of students deserves understanding of their school’s complete history—the multiple institutions that merged, the communities they served, the achievements they celebrated, and the traditions they maintained. Alumni from predecessor schools deserve continued connection to their educational heritage rather than seeing it erased or forgotten.

Modern recognition systems like Rocket Alumni Solutions provide powerful tools for consolidated districts to preserve comprehensive heritage from all predecessor schools. By accommodating unlimited content, enabling searchable exploration, and providing both physical and web-based access, these systems ensure complete district history remains accessible and celebrated rather than being limited by physical space constraints that force selective recognition.

Whether your district resulted from consolidation decades ago or faces potential merger today, understanding consolidation’s history provides valuable context for navigating complex decisions balancing educational quality, fiscal responsibility, and community identity. The consolidation story continues, with each district writing its own chapter in the ongoing evolution of American education.

Book a demo to discover how your consolidated district can preserve and celebrate the complete heritage from all predecessor schools through comprehensive digital recognition displays.