Every school, organization, and community contains a treasure trove of stories waiting to be told—firsthand accounts from alumni, faculty, staff, and community members who witnessed pivotal moments, pioneered programs, overcame challenges, and shaped institutional identity. Oral history interviews capture these irreplaceable narratives before they’re lost to time, preserving authentic voices and perspectives that bring history to life in ways that written records alone cannot achieve.

Whether you’re an educator seeking to document your school’s evolution, an alumni director building engagement through storytelling, or an institutional archivist preserving heritage, oral history interviews offer powerful tools for capturing, preserving, and sharing community narratives. When combined with modern digital recognition platforms, these recorded stories transform from archived files into living, accessible resources that engage current students, reconnect alumni, and strengthen community bonds across generations.

This comprehensive guide explores oral history interview best practices, practical implementation strategies for educational settings, preservation techniques, and innovative approaches for integrating oral histories into digital recognition displays that make these invaluable stories accessible to your entire community.

Understanding Oral History: Purpose and Value

Oral history represents a distinct historical methodology focused on recording and preserving firsthand accounts and personal narratives through recorded interviews. Unlike written memoirs or institutional documents, oral histories capture the nuance, emotion, and individual perspective that make history personal and relatable.

What Makes Oral History Unique?

Oral history interviews differ from standard historical documentation through several distinguishing characteristics that enhance their value for educational institutions and community organizations.

Personal Voice and Authenticity: Oral histories preserve the actual words, speech patterns, and emotional tone of narrators, creating authentic connections impossible to replicate through written summaries. Hearing a 1950s graduate describe their school experience in their own voice carries impact that transcripts alone cannot convey.

Lived Experience and Perspective: These interviews capture subjective experiences, personal interpretations, and individual viewpoints that institutional records typically overlook. While official documents might note that a school integrated in 1965, oral histories from students who lived through that transition reveal the human experience behind historical facts.

Memory and Reflection: Unlike contemporary documents created during events, oral histories benefit from reflection and perspective that only time provides. Interviewees can assess significance, identify lasting impacts, and connect experiences to broader patterns in ways impossible during the moment.

Under-documented Narratives: Oral history particularly excels at capturing stories from communities and individuals whose experiences may not appear in traditional archives—students from marginalized groups, support staff, volunteers, or community members whose contributions might otherwise go unrecognized.

For schools and organizations, oral history programs serve multiple valuable purposes including documenting institutional evolution and cultural change, preserving memories of significant events or transitions, honoring contributions from diverse community members, creating educational resources for current students, strengthening alumni engagement through storytelling, and building institutional identity and community connection.

Educational Benefits of Oral History Programs

Beyond historical preservation, oral history initiatives create significant educational opportunities for students, educators, and communities.

Student Learning Outcomes: When students participate in oral history projects, they develop critical research and preparation skills, practice active listening and questioning techniques, learn interview and interpersonal communication abilities, gain historical thinking and analysis capabilities, understand diverse perspectives and experiences, and develop digital literacy through recording and editing.

Many educators incorporate oral history projects into curricula, having students interview alumni, community elders, or family members as practical applications of historical methodology while creating valuable institutional resources.

Community Engagement: Oral history programs strengthen bonds between institutions and their communities by inviting participation from alumni and community members, validating individual experiences and contributions, creating intergenerational connections and dialogue, demonstrating institutional commitment to inclusive history, and providing accessible entry points for community involvement.

These engagement benefits support broader institutional goals in alumni relations and community building while generating content that can enhance recognition programs and institutional storytelling.

Historical Preservation: Oral histories preserve irreplaceable information including personal accounts of significant institutional events, details about daily life and culture across eras, explanations of decisions and motivations behind changes, stories about individuals not documented elsewhere, and context for understanding institutional evolution.

Without systematic oral history efforts, these details often disappear as generations pass, leaving future historians with incomplete understanding of institutional heritage.

Planning Your Oral History Program

Successful oral history initiatives require thoughtful planning that addresses project goals, target narrators, interview protocols, technical requirements, and preservation strategies.

Defining Project Scope and Goals

Clear project definition ensures focused, manageable initiatives that achieve meaningful results rather than becoming overwhelming undertakings that stall.

Project Focus: Successful oral history programs typically center on specific themes or topics rather than attempting to document everything. Focus areas might include significant institutional events or anniversaries, specific time periods or eras of institutional history, particular programs, departments, or activities, experiences of specific demographic groups, responses to specific challenges or changes, or contributions from particular categories of community members.

Focused projects generate coherent bodies of work with clear narratives rather than disconnected collections of random recollections.

Intended Outcomes and Uses: Clarify how oral histories will be used—creating institutional archives, developing educational resources, enhancing anniversary or reunion programs, supporting digital recognition displays, generating content for publications or websites, or supporting research about institutional history.

Clear outcome definitions help determine appropriate interview approaches, recording quality requirements, and preservation formats.

Timeline and Resources: Realistic planning addresses staff time for planning and coordination, interviewer training and preparation, interview scheduling and conducting, recording equipment and technical support, transcription and editing resources, archival storage and preservation systems, and promotion and access development.

Most schools find that starting with modest pilot programs—perhaps 5-10 interviews focused on specific themes—builds capacity and refines processes before expanding to larger initiatives.

Identifying and Recruiting Narrators

Strategic narrator selection ensures diverse perspectives while focusing on individuals whose experiences align with project goals and themes.

Selection Criteria: Consider narrators who experienced significant institutional events firsthand, represent diverse demographic groups and perspectives, held unique positions or roles within the community, witnessed important transitions or cultural shifts, possessed specialized knowledge about specific programs, or can speak to under-documented aspects of institutional history.

Diversity in narrator selection creates richer, more complete historical records that represent multiple perspectives rather than singular viewpoints.

Recruitment Approaches: Effective recruitment strategies include direct personal invitations to specific individuals, announcements through alumni communications and newsletters, presentations at reunion events or community gatherings, partnerships with alumni chapters or affinity groups, social media campaigns seeking narrator volunteers, and snowball sampling where interviewees recommend additional narrators.

Personal invitations typically generate higher response rates than general calls for volunteers, particularly when explaining how individuals’ specific experiences connect to project goals.

Narrator Preparation: Once narrators agree to participate, provide clear information about interview purposes and intended uses, estimated time commitments and scheduling, interview formats and typical question areas, recording and preservation approaches, how recorded materials will be accessed and used, and consent and release requirements.

This transparency helps narrators prepare mentally for interviews while ensuring informed consent about how their stories will be preserved and shared.

Developing Interview Questions and Approaches

Thoughtful interview preparation generates richer, more substantive narratives while ensuring efficient use of limited interview time.

Question Development: Effective oral history interviews combine structured preparation with flexible conversation that follows interesting narrative directions. Question frameworks typically include biographical background establishing context, chronological life narrative covering relevant time periods, specific event or experience descriptions, reflection on significance and meaning, and connections to broader institutional or cultural themes.

Open-ended questions that invite storytelling generate richer responses than yes/no questions or leading questions that suggest expected answers. Rather than “Did you enjoy your time here?”, ask “What do you remember most clearly about your time here?” or “What experiences shaped your perspective during those years?”

Interview Techniques: Skilled oral history interviewers practice active listening that encourages detailed narratives, comfortable silence allowing narrators time to remember and reflect, follow-up questions that probe interesting details, gentle redirection when conversations drift too far from relevant topics, and sensitivity to emotional or difficult memories.

The goal is facilitating narrators’ storytelling rather than conducting interrogations or directing conversations toward predetermined conclusions.

Ethical Considerations: Oral history practice requires respecting narrator dignity and autonomy, obtaining informed consent for recording and preservation, honoring confidentiality requests and sensitivities, acknowledging emotional difficulty of some recollections, providing opportunities to review and clarify recordings, and clear communication about access and use of materials.

The Oral History Association provides comprehensive ethical guidelines addressing these considerations for practitioners conducting interview projects.

Technical Aspects: Recording and Equipment

Quality recordings ensure that oral histories remain accessible and usable over time while meeting preservation standards that maintain long-term value.

Recording Equipment and Setup

Modern recording technology provides accessible, affordable options for capturing high-quality oral history interviews without requiring professional studio facilities.

Audio Recording Equipment: Basic oral history recording requires reliable digital audio recorders or quality microphones connected to computers or tablets, backup recording device for redundancy, headphones for monitoring recording quality, and appropriate storage for raw recording files.

Many programs successfully use professional-grade digital recorders ($100-300) that provide excellent audio quality without complex setup requirements. Smartphone recording apps can serve basic needs but generally provide less reliable quality than dedicated equipment.

Video Recording Considerations: Video recording adds visual dimension to oral histories but requires additional equipment including quality video cameras or high-end smartphones, external microphones for clear audio, appropriate lighting equipment, tripods or stabilization equipment, and significantly more storage and editing capacity.

Institutions should weigh video benefits against additional complexity—video captures visual cues and emotions but requires substantially more technical expertise, storage capacity, and processing time than audio-only recording.

Recording Environment: Quality recordings require quiet spaces with minimal background noise, comfortable seating arrangements for extended conversations, appropriate temperature and lighting, and minimal disruptions or interruptions.

Many schools conduct interviews in library conference rooms, empty classrooms after hours, or quiet office spaces that provide controlled environments supporting quality recording without requiring specialized studios.

Technical Testing: Before each interview session, test all recording equipment for functionality, verify adequate storage space for extended recording, check battery levels and have backup power available, test microphone placement and audio levels, and create backup recording simultaneously when possible.

Technical failures during interviews create frustration and may result in lost narratives if narrators cannot reschedule or recreate spontaneous recollections.

Recording Best Practices

Systematic approaches ensure consistent quality across interview collections while maintaining professional standards that support long-term preservation.

Pre-Interview Procedures: Professional oral history practice includes written consent forms signed before recording begins, biographical data collection for contextual documentation, technical checks ensuring equipment functionality, relaxed conversation helping narrators feel comfortable, and clear explanation of interview format and expectations.

These preparatory steps establish professionalism while putting narrators at ease before recording begins.

During Interview: Maintain recording awareness by monitoring levels, periodically checking equipment continues recording, noting technical issues or disruptions for later reference, managing file sizes on equipment with limited capacity, and maintaining presence and engagement despite technical monitoring.

Post-Interview Procedures: After completing recordings, verify files saved correctly and are accessible, create backup copies immediately, document interview with basic metadata (narrator, date, location, interviewer), note any technical issues affecting recording quality, and provide narrators information about next steps and when they might review recordings.

Immediate backup creation protects against equipment failure, file corruption, or accidental deletion before files are properly archived.

Processing and Preservation

Raw recordings require processing before becoming accessible, usable historical resources that serve research, educational, and engagement purposes.

Transcription Approaches

Transcripts transform audio recordings into text documents that facilitate searching, browsing, and accessing interview content without requiring listening to entire recordings.

Transcription Options: Complete verbatim transcripts capture every word, pause, and speech pattern with high accuracy but require substantial time and resources—typically 4-6 hours of transcription work per hour of recording. Edited transcripts remove false starts, repetitions, and verbal tics while maintaining content accuracy, requiring less time while remaining highly accurate. Summary abstracts provide paragraph summaries of interview content organized by topic, allowing quick content assessment while omitting extensive detail.

Many oral history programs use edited transcripts striking balance between accuracy and resource requirements. Automated transcription services like Otter.ai, Rev.com, or Trint provide initial drafts that human editors review and correct, significantly reducing transcription costs and time while maintaining adequate accuracy.

Transcription Standards: Professional transcription typically includes narrator and interviewer identification, time stamps at regular intervals, notation of significant pauses, emotions, or laughter, clarification of unclear words or phrases, and correction of obvious verbal mistakes while preserving meaning.

Consistent standards across transcript collections facilitate use by different readers and researchers over time.

Review and Correction: Narrators should have opportunities to review transcripts, correct factual errors or unclear statements, clarify ambiguous passages, add context or explanation where needed, and identify any material they prefer not be publicly accessible.

This review process respects narrator agency while improving transcript accuracy and completeness.

Metadata and Documentation

Comprehensive documentation ensures oral histories remain understandable and usable decades after creation, even by individuals unfamiliar with original project contexts.

Essential Metadata Elements: Each oral history should include narrator identifying information (name, birth year, connection to institution), interview date, location, and duration, interviewer identification, project or collection identification, subject headings and keywords describing content, transcript availability and format, access restrictions if any, and technical information about recording format and quality.

This metadata enables searching, browsing, and filtering interview collections while providing context necessary for interpretation.

Contextual Documentation: Project-level documentation should explain initiative purpose and goals, selection criteria for narrators, interview question frameworks and approaches, consent and release information, funding sources and project partners, and preservation and access policies.

This contextual information helps future users understand collection scope, limitations, and appropriate uses.

Digital Preservation and Access

Long-term preservation requires systematic approaches ensuring oral histories remain accessible despite technological change and physical media degradation.

File Format Standards: Preservation best practices recommend saving master recordings in uncompressed formats (WAV or AIFF) that preserve complete audio information, creating access copies in compressed formats (MP3) for easier distribution and streaming, and maintaining multiple backup copies in geographically separate locations.

Storage Solutions: Institutions should implement secure digital storage systems including dedicated archival storage (not just general file servers), regular automated backup procedures, geographic redundancy protecting against local disasters, and periodic migration to new storage media and formats.

Cloud-based storage solutions provide cost-effective options for many schools while ensuring professional-grade backup and redundancy.

Access Systems: Making oral histories accessible requires intuitive browse and search interfaces, transcript integration enabling content discovery, metadata display providing context, appropriate access controls respecting any restrictions, and integration with institutional websites or archives.

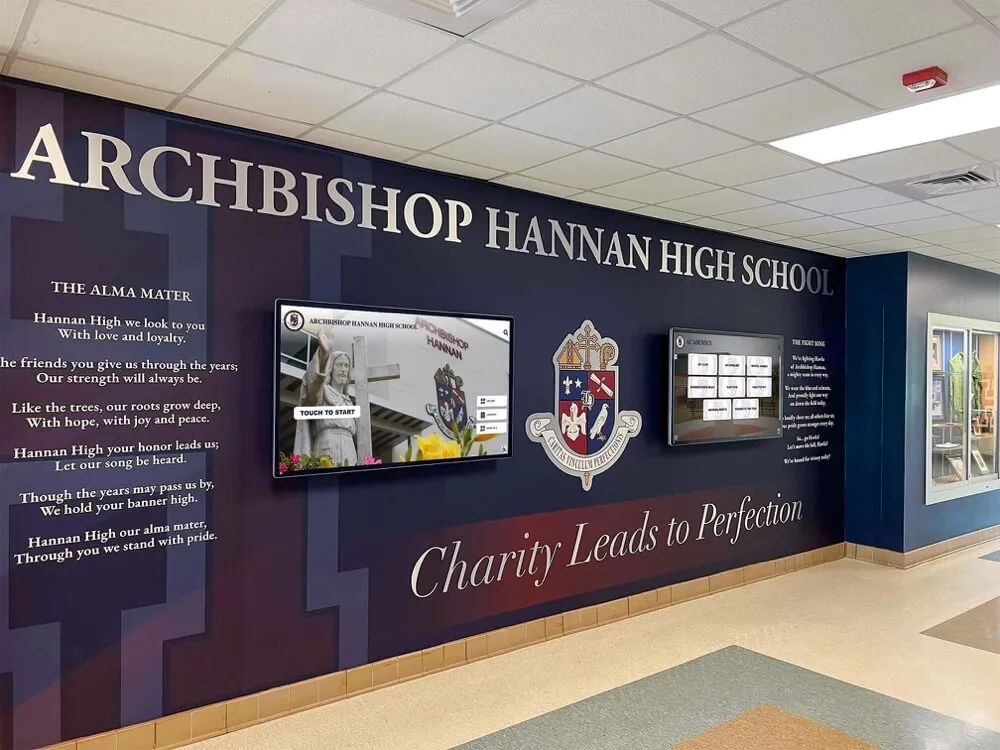

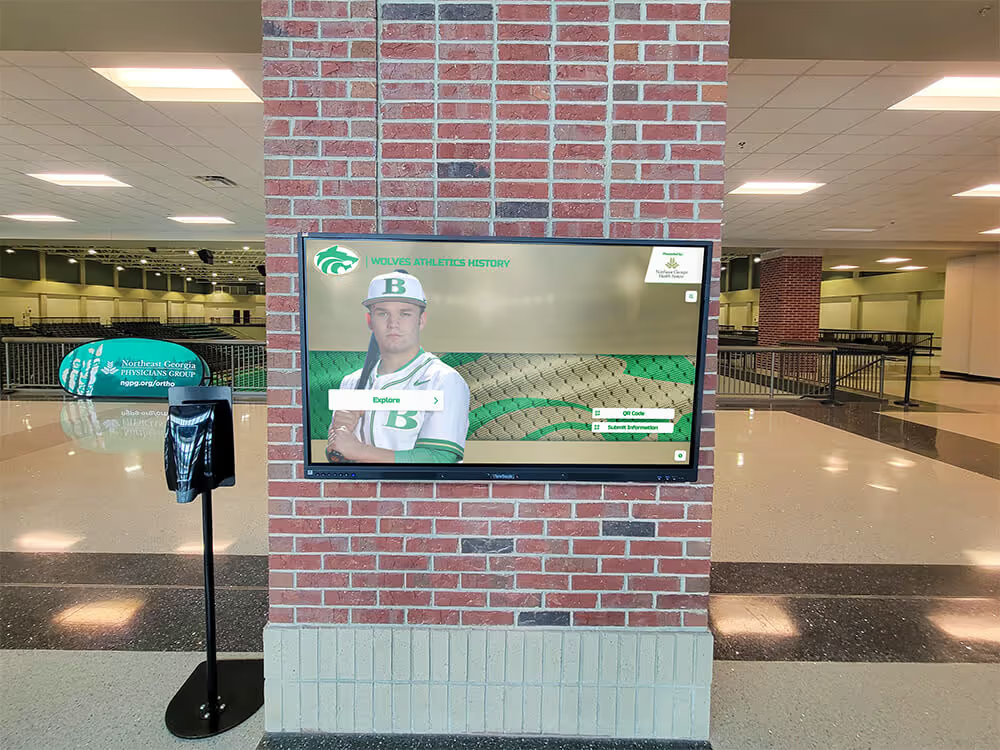

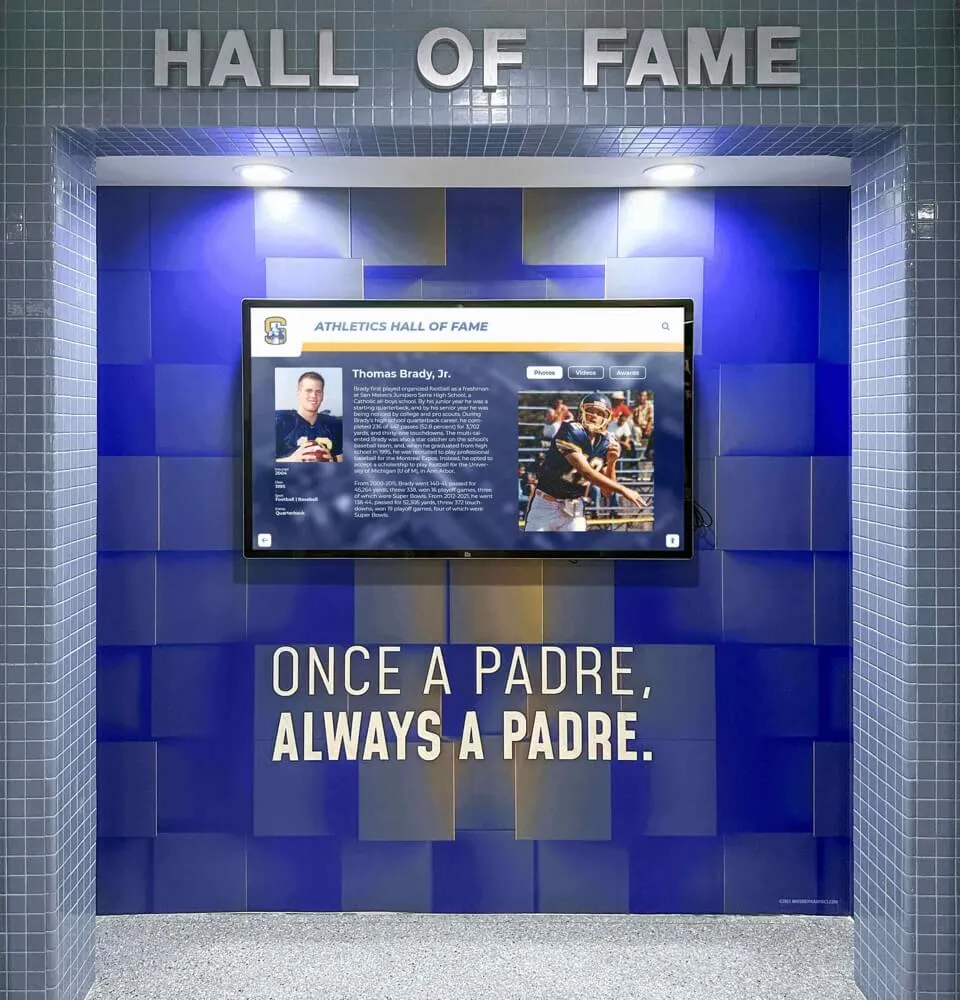

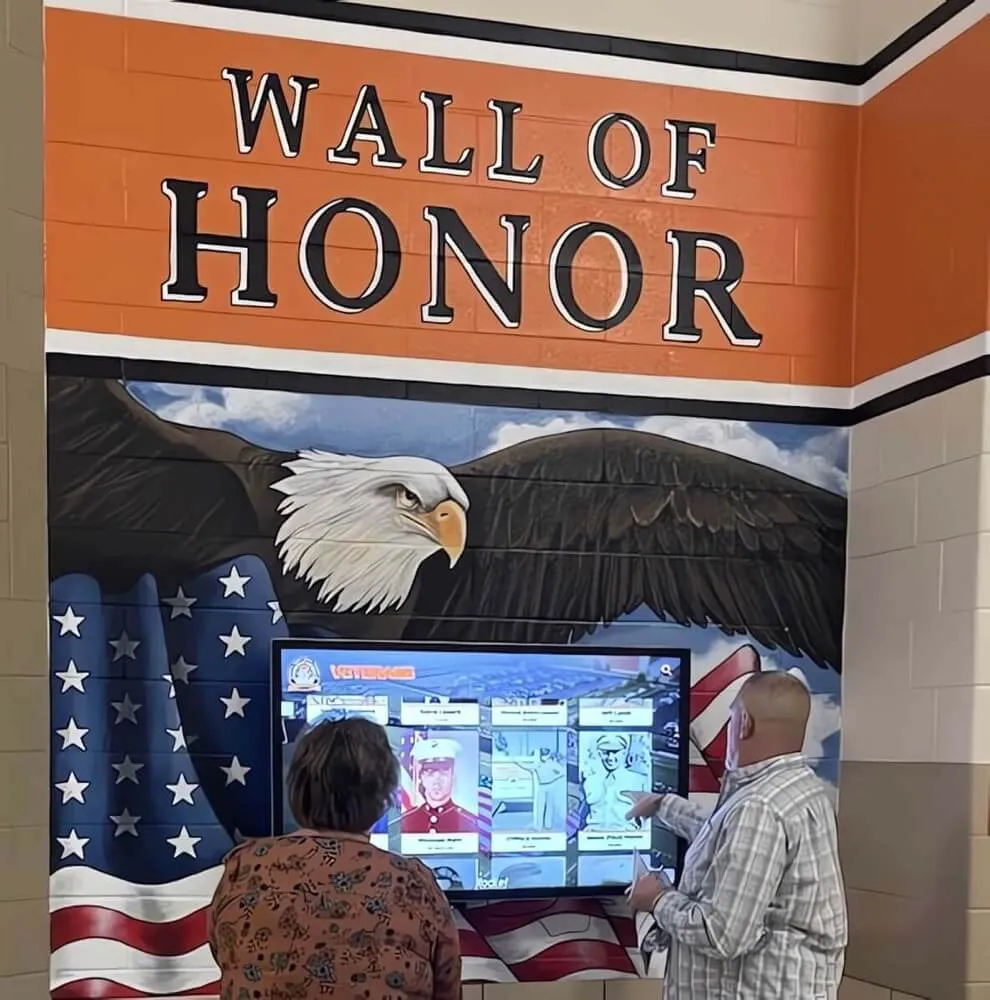

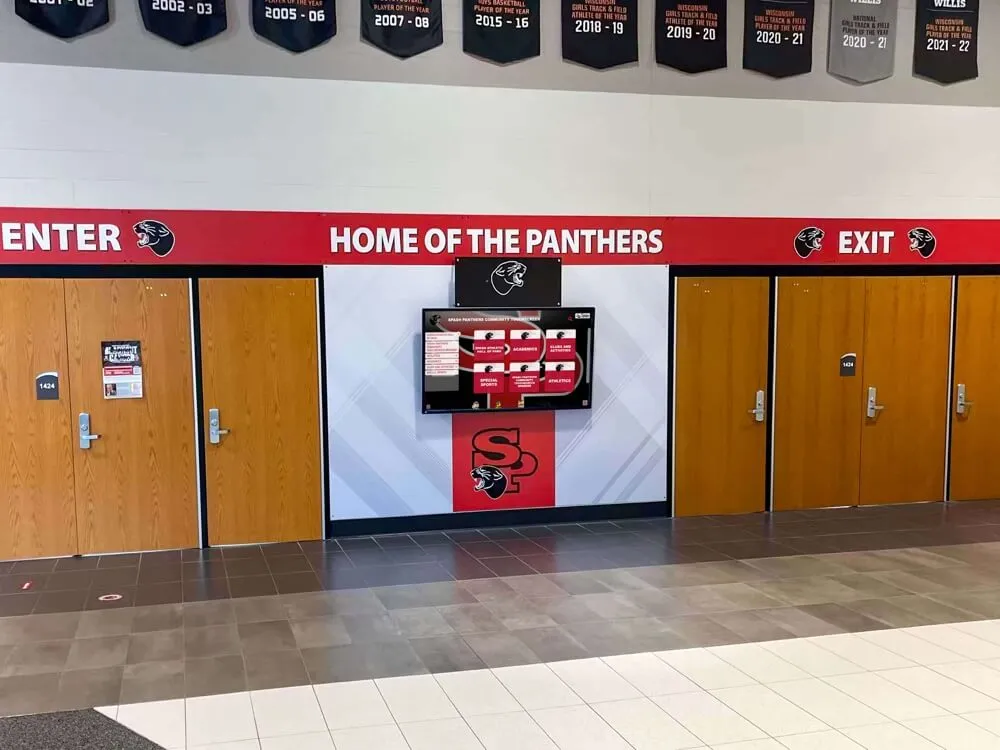

Some schools integrate oral history excerpts into digital recognition displays, allowing visitors to hear alumni voices describing their experiences, memories, and reflections alongside photos and biographical information. This integration transforms static recognition into living storytelling that creates emotional connections between past and present community members.

Integrating Oral Histories with Digital Recognition

While traditional archives make oral histories available to researchers and interested community members, integration with digital recognition systems dramatically expands accessibility and engagement with these invaluable narratives.

Multimedia Recognition Displays

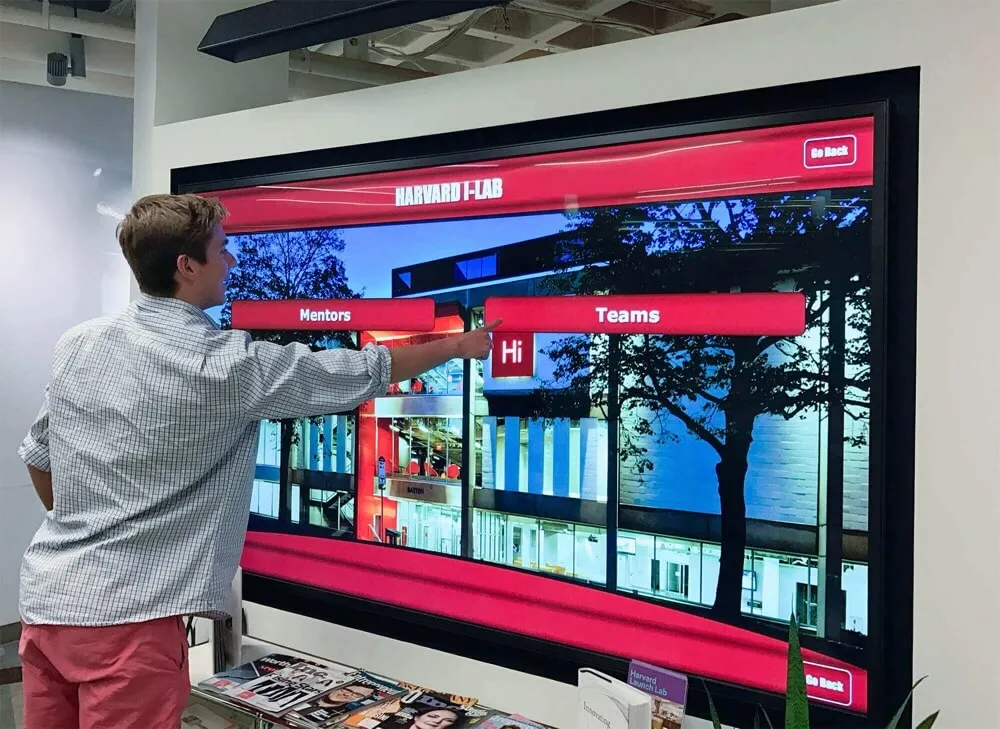

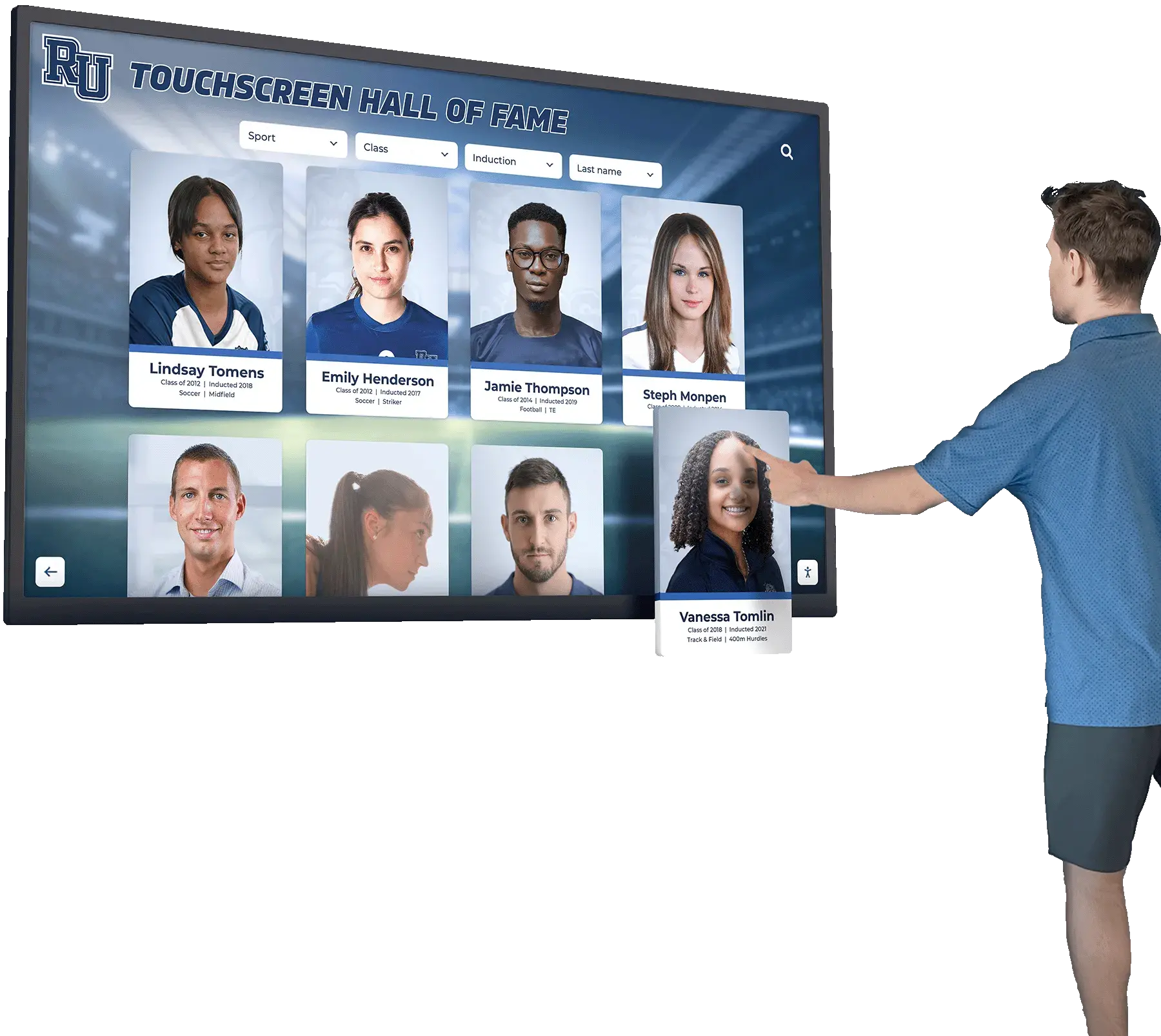

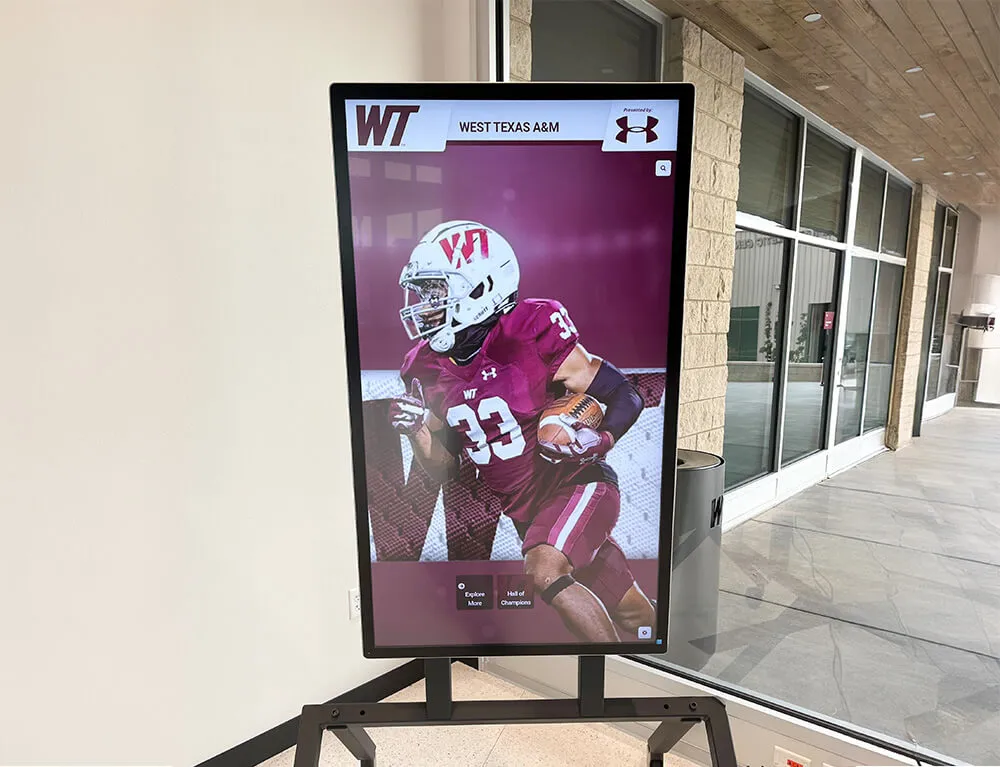

Modern recognition platforms enable rich multimedia presentations combining photos, text, video, and audio into compelling interactive experiences that honor individuals while sharing their stories in their own voices.

Audio Excerpt Integration: Interactive digital displays can feature selected audio clips where honorees describe significant experiences, reflect on their achievements, share advice for current students, explain how their education influenced their lives, or describe institutional culture and traditions from their era.

These audio elements add authentic voice and personality to recognition profiles, creating emotional engagement impossible with photos and text alone. Hearing a 1960s alumnus describe playing on championship teams or a pioneering faculty member explain establishing new programs brings history alive in uniquely powerful ways.

Video Testimonial Incorporation: When oral history projects include video recording, recognition displays can feature video clips showing honorees as they share stories and reflections. Visual elements enhance connection—facial expressions, gestures, and emotional reactions communicate meanings beyond words alone.

The creating video content for digital recognition guide explores strategies for incorporating video effectively into recognition programs.

Transcript Integration: Full or excerpted transcripts accompanying audio or video allow visitors who prefer reading to engage with oral history content while providing accessibility for hearing-impaired visitors. Searchable transcripts also enable finding specific content within extensive interview collections.

Thematic Organization: Digital recognition systems can organize oral history content by themes, time periods, topics, or experiences rather than only by individual honorees. This organization allows visitors to explore experiences of students during specific decades, perspectives on institutional traditions, or recollections about significant events from multiple viewpoints.

Enhancing Alumni Engagement

Oral histories create powerful alumni engagement tools when shared through accessible digital platforms that extend reach beyond physical campus visitors.

Web-Accessible Story Collections: Alumni anywhere in the world can explore oral histories through institutional websites, allowing distant graduates to reconnect with campus experiences and peers. This accessibility particularly benefits alumni who cannot easily visit campus but remain interested in institutional community and history.

Social Media Sharing: Short audio or video clips from oral histories create highly engaging social media content that generates comments, shares, and emotional responses. Alumni who might not click through to formal oral history archives will engage with story excerpts appearing in their social media feeds, particularly when content connects to their own experiences or classmates they remember.

Solutions like Rocket Alumni Solutions provide alumni engagement platforms that integrate recognition, storytelling, and community-building features supporting comprehensive engagement strategies.

Reunion and Event Integration: Oral histories can enhance reunion programming by featuring relevant stories from graduating class members, creating “then and now” comparisons with current campus, providing discussion prompts for reunion attendees, or inspiring alumni to share their own memories and updates.

Educational Applications

Oral history collections serve valuable educational purposes when integrated into curricula and learning experiences for current students.

History and Social Studies: Students studying institutional or community history can analyze oral histories as primary source materials, compare multiple perspectives on same events, identify themes and patterns across narratives, and practice historical thinking skills with authentic materials.

Research Projects: Oral history collections provide research resources for student papers, projects, and presentations exploring institutional heritage, cultural evolution, or specific events and time periods.

Inspiration and Role Models: Hearing alumni describe their educational journeys, career paths, challenges overcome, and advice for current students provides inspiration and guidance from relatable role models who walked similar paths.

Cultural Preservation: For schools serving specific cultural communities, oral histories preserve cultural traditions, languages, and experiences that might otherwise be lost as generations pass, creating invaluable educational and cultural resources.

The school history timeline guide explores additional approaches for making institutional heritage accessible and engaging for current students and community members.

Building Sustainable Oral History Programs

Long-term success requires establishing manageable workflows, securing ongoing support, and creating organizational structures that ensure programs continue beyond initial enthusiasm.

Establishing Organizational Infrastructure

Sustainable programs require clear structures and responsibilities rather than depending on individual champions whose departure might end initiatives.

Program Leadership: Designate clear leadership responsibility for oral history initiatives—typically staff members from libraries, archives, alumni relations, or institutional advancement. These leaders coordinate planning, recruit and train volunteers or student participants, oversee technical aspects, maintain collections and archives, and promote access and engagement.

Volunteer and Student Involvement: Many successful programs engage volunteers including alumni volunteers serving as interviewers, student interns or class projects conducting interviews, retired faculty or staff assisting with coordination, and community volunteers helping with transcription or metadata development.

This volunteer engagement reduces staff burden while creating community investment in program success. Student involvement particularly provides learning opportunities while generating valuable content—many programs successfully structure oral history initiatives as semester-long class projects where students learn methodology while building institutional collections.

Technical Support: Identify reliable technical support for equipment maintenance and troubleshooting, recording and editing software assistance, digital storage and backup systems, and web access platform development and maintenance.

Many schools leverage existing IT or library staff expertise rather than requiring dedicated oral history technical positions.

Funding and Resource Development

Sustainable programs require ongoing resources beyond initial startup enthusiasm and funding.

Budget Requirements: Annual operating budgets should address equipment maintenance and replacement, storage and preservation systems, transcription services or software subscriptions, staff time or student compensation, promotion and access development, and program coordination and administration.

Funding Sources: Potential support includes general operating budgets through libraries or archives, alumni association support for alumni engagement programs, special project grants from foundations, donor-funded endowments supporting heritage preservation, parent or community fundraising campaigns, or student activity fees supporting student learning initiatives.

Many institutions successfully launch pilot programs with modest grant funding, then secure ongoing operational support once programs demonstrate value and generate community enthusiasm.

In-Kind Support: Non-monetary resources can significantly extend limited budgets including equipment loans from technology departments, volunteer labor from community members, student work through class projects or internships, software subscriptions through institutional licenses, and technical expertise from staff across campus departments.

Promotion and Community Engagement

Even excellent oral history collections provide limited value if communities don’t know they exist or how to access them.

Launch Events: Formal program launches or special presentations create awareness and generate excitement including public unveiling of initial interview collections, panel discussions with featured narrators, presentations about oral history methodology and value, demonstrations of access platforms and search capabilities, and invitations for additional community members to participate as future narrators.

Ongoing Communication: Maintain visibility through regular features in alumni publications, social media posts highlighting individual stories or clips, website features and blog posts, presentations at reunion events, and integration into campus tours and visitor experiences.

Recognition for Participants: Honor narrators who share their stories and volunteer interviewers who conduct interviews through public acknowledgment in collections and publications, invitations to special events and programs, and certificates or small tokens of appreciation.

This recognition encourages ongoing participation while demonstrating institutional gratitude for contributions to heritage preservation.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Oral history programs face predictable challenges that most initiatives encounter. Understanding these obstacles and proven solutions helps programs navigate difficulties successfully.

Time and Resource Constraints

Challenge: Oral history work requires significant time for planning, interviewing, processing, and preservation—often more than initial estimates suggest. Small staffs struggle to maintain programs alongside other responsibilities.

Solutions: Start with focused pilot projects rather than comprehensive programs, establish realistic timelines that account for genuine capacity, leverage volunteer and student labor where appropriate, prioritize quality over quantity in early phases, and use technology tools that reduce processing time.

Technical Difficulties

Challenge: Recording equipment malfunctions, file corruption, storage limitations, and software learning curves create frustration and potential data loss.

Solutions: Invest in reliable professional equipment rather than consumer-grade alternatives, maintain backup recording systems, implement immediate file backup procedures, provide adequate training for technical aspects, and establish technical support relationships before problems occur.

Narrator Recruitment

Challenge: Identifying and recruiting suitable narrators can prove difficult, particularly for historically underrepresented groups whose stories are most needed for comprehensive collections.

Solutions: Use personal outreach rather than only general announcements, clearly explain how individual stories connect to project goals, address potential concerns about memory quality or story significance, partner with affinity groups and alumni chapters serving specific demographics, and consider compensating narrators with modest honoraria when appropriate.

Transcription Backlogs

Challenge: Transcription work creates bottlenecks as recordings accumulate faster than processing capacity allows.

Solutions: Use automated transcription services for initial drafts that require less time to edit than full manual transcription, train multiple volunteers or students to share workload, accept that not every interview requires complete verbatim transcription—summary abstracts serve many purposes adequately, and phase interview collection to allow processing time before conducting additional interviews.

Access and Discovery

Challenge: Valuable oral histories provide little benefit if community members don’t know collections exist or cannot easily find relevant content.

Solutions: Integrate oral history clips into digital recognition displays and campus installations that reach general visitors, feature compelling excerpts on institutional websites and social media, develop intuitive search interfaces with robust metadata, promote collections through alumni communications and reunion programs, and create topical compilations addressing specific themes or events that interest particular audiences.

Bring Your Oral Histories to Life with Digital Recognition

Rocket Alumni Solutions specializes in interactive digital recognition systems that showcase institutional heritage through multimedia storytelling. Our platforms integrate audio clips, video testimonials, photographs, and biographical information into engaging displays that transform archived oral histories into accessible, compelling community resources.

Whether you're launching your first oral history initiative or seeking better ways to share existing collections, we'll help you create recognition displays that honor your community's stories while strengthening bonds between past, present, and future generations.

Contact us today to learn how digital recognition can amplify your oral history program's impact and accessibility.

Conclusion: Preserving Voices, Strengthening Communities

Oral history interviews capture irreplaceable narratives that bring institutional heritage to life through authentic voices sharing personal experiences, memories, and reflections. These recorded stories preserve details and perspectives that written records alone cannot convey while creating emotional connections between community members across generations.

For schools, universities, and organizations, oral history programs serve multiple valuable purposes—documenting institutional evolution, honoring diverse contributions, supporting educational objectives, and strengthening alumni engagement. When thoughtfully planned and systematically implemented, these initiatives create lasting resources that will serve communities for generations.

The integration of oral histories with modern digital recognition platforms dramatically expands accessibility and impact. Rather than residing in archives accessed by occasional researchers, oral history excerpts featured in interactive displays and recognition programs reach thousands of community members, students, and visitors who experience institutional heritage through the authentic voices of those who shaped it.

As technology continues evolving, opportunities for preserving and sharing oral histories will only expand. Schools and organizations that establish oral history programs today create invaluable resources that will strengthen community identity, inspire future generations, and preserve authentic narratives for posterity. Start your oral history initiative today, and ensure that the voices shaping your institutional story are preserved and celebrated for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should oral history interviews typically be?

Oral history interview length varies based on project goals, narrator availability, and content depth desired. Most interviews run 60-90 minutes, providing sufficient time to cover biographical background, explore significant experiences in detail, and allow narrators time to remember and reflect without rushing. Some comprehensive life history interviews extend to 2-3 hours or even multiple sessions spread across several days. However, longer interviews require more processing time and may fatigue both narrators and interviewers. For school-based projects, 45-60 minute interviews often provide optimal balance—long enough for substantive content but manageable for student interviewers and volunteer narrators. Focus questions tightly on relevant topics rather than attempting exhaustive life histories to maximize limited time.

Do we need special permission or consent forms for oral history interviews?

Yes, professional oral history practice requires written consent from narrators before recording begins. Consent forms should explain interview purposes and intended uses, describe how recordings will be preserved and accessed, clarify intellectual property rights (typically assigning rights to institution while acknowledging narrator contributions), address any access restrictions or confidentiality requests, obtain permission for specific uses (archival preservation, website publication, educational purposes), and provide contact information for questions or concerns. These forms protect both institutions and narrators by establishing clear understanding about how interviews will be used. The Oral History Association provides sample consent form templates that many programs adapt for their specific contexts. Consult institutional legal counsel when developing consent forms to ensure they address relevant regulations and institutional policies.

Can we conduct oral history interviews remotely via video call?

Yes, remote oral history interviews via video conferencing platforms have become increasingly common and effective, particularly for interviewing distant alumni or during circumstances that limit in-person meetings. Remote interviews offer several advantages including eliminating geographic barriers to narrator participation, reducing scheduling conflicts without travel time, enabling comfortable participation from narrators’ own spaces, and allowing easy screen recording for documentation. However, remote interviews also present challenges including potential technical difficulties disrupting conversations, reduced interpersonal connection compared to in-person meetings, audio quality sometimes inferior to dedicated recording equipment, and the need for both parties to have reliable internet access and appropriate technology. When conducting remote interviews, test technology beforehand, use video platforms that allow local recording for backup, minimize background noise and distractions, and plan for technical difficulties by having backup communication methods available.

What do we do if oral history narrators share inaccurate information or their memories contradict documented facts?

Memory imperfection represents an inherent characteristic of oral history rather than a flaw to eliminate. Oral histories capture subjective experience and individual perspective, which may differ from objective facts or other people’s recollections of the same events. When factual inaccuracies appear, consider these approaches: note discrepancies in transcript footnotes or metadata without editing narrator’s words, cross-reference multiple oral histories about same events to capture varied perspectives, use interviews alongside documentary evidence rather than as sole historical sources, and view different recollections as revealing how individuals experienced and interpreted events rather than as errors needing correction. The value of oral history often lies precisely in personal interpretation and subjective experience rather than only in factual accuracy. However, when significant factual errors appear (incorrect dates, misidentified individuals), annotate transcripts noting corrections while preserving original narration.

How can we encourage reluctant community members who don’t think their stories matter to participate in oral history programs?

Many potential narrators decline participation believing their experiences weren’t important enough or interesting enough to record. Overcome this reluctance by explaining how seemingly ordinary experiences provide invaluable historical perspective, emphasizing that “everyday” recollections document cultural context and common experiences that formal records overlook, noting that future researchers value diverse perspectives including those of students, staff, and community members alongside traditional leaders, sharing examples of how past participants found interview processes meaningful and enjoyable, and framing participation as contribution to institutional heritage and gift to future generations. Personal invitation works more effectively than general calls for volunteers—explain specifically why the individual’s perspective matters and what unique insights their experiences might provide. Sometimes reluctant narrators become enthusiastic participants once interviews begin and they realize their stories genuinely interest interviewers.

What technical skills do interviewers need to conduct oral history interviews?

Effective oral history interviewing requires certain skills, but most can be learned through training and practice rather than requiring advanced expertise. Essential interviewer capabilities include active listening skills and genuine curiosity about narrators’ experiences, comfort with recording technology and basic troubleshooting, ability to develop thoughtful questions and follow interesting narrative threads, interpersonal skills creating comfortable environments for sharing, patience allowing narrators time to remember and reflect, and cultural sensitivity respecting diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Many successful programs train volunteer interviewers or students through workshops covering oral history methodology and ethics, interview techniques and question strategies, technical recording procedures, and practice interviews with feedback. Initial training followed by supervised practice typically prepares interviewers adequately for independent work. Pairing less experienced interviewers with mentors for early interviews builds confidence while ensuring quality.

How do we balance preserving complete oral histories while making them accessible to general audiences who won’t listen to hour-long interviews?

Most oral history users prefer accessing relevant excerpts rather than complete interviews. Balance comprehensive preservation with accessible use through these strategies: preserve complete unedited recordings in archival storage for researchers needing full context, create detailed metadata and time-stamped transcripts enabling users to locate relevant sections without listening to entire interviews, develop thematic compilations or highlight reels featuring clips about specific topics, integrate compelling excerpts into digital recognition displays and institutional websites while noting that complete interviews exist for interested users, and promote particularly compelling or historically significant interviews through features and special presentations. Most users appreciate curated access helping them quickly find relevant content, while serious researchers value complete archives for comprehensive analysis. Modern digital platforms enable both comprehensive preservation and selective access, ensuring oral histories serve varied purposes and audiences effectively.