Every fraternity and sorority has a story—a rich tapestry woven from founding moments, transformative leaders, cherished traditions, and generations of members whose lives were shaped by their Greek experience. These organizational histories represent more than nostalgic reminiscence; they document student life evolution, women’s higher education progress, leadership development traditions, and community values that have influenced millions of college graduates across more than two centuries.

Yet fraternity and sorority history is at risk. Across thousands of chapters nationwide, irreplaceable historical materials deteriorate in damp basements, disappear during chapter house moves, get discarded during leadership transitions, or simply fade from institutional memory as knowledgeable alumni age. Composite photographs yellow and crack, meeting minutes written in fountain pen become illegible, scrapbooks documenting decades of events crumble, and oral traditions fade when no one documents them. Without intentional preservation efforts, this rich heritage vanishes permanently—a loss not only for individual organizations but for broader historical understanding of American higher education and student culture.

This comprehensive guide explores practical, actionable strategies for preserving fraternity and sorority history. Whether you’re a chapter historian managing current records, an alumni volunteer digitizing decades of materials, a house corporation trustee responsible for organizational archives, or a Greek life professional supporting multiple chapters, you’ll discover proven approaches for protecting your organization’s heritage while making it accessible to current and future generations.

The preservation challenge extends beyond simply storing old materials. Effective heritage conservation requires understanding what materials have historical value, implementing appropriate preservation methods for different artifact types, creating accessible digital archives, documenting oral histories before they’re lost, establishing sustainable record-keeping systems, and engaging members and alumni in ongoing stewardship. Organizations that approach preservation strategically create living archives that strengthen member connection, support alumni engagement, inform current leadership, and ensure their unique stories survive for future generations.

Understanding What Fraternity and Sorority History to Preserve

Before implementing preservation strategies, successful programs require clarity about what materials have enduring historical value. Greek organizations produce enormous volumes of documents, photographs, and artifacts—not all equally worthy of permanent preservation. Strategic selection ensures limited resources focus on materials with greatest historical significance.

Official Organizational Records

These documents form the core of any fraternity or sorority archive:

Charter and Founding Documents: Original chapter charters, national organization charters, incorporation papers, and founding correspondence document your chapter’s official establishment. These irreplaceable legal and historical documents should receive highest preservation priority.

Meeting Minutes and Official Proceedings: Regular chapter meeting minutes, executive board proceedings, alumni association meetings, and house corporation records document decision-making, leadership actions, and organizational evolution over time. Complete minute books provide invaluable insight into how your chapter addressed challenges and opportunities across decades.

Constitution and Bylaws: Historical versions of chapter constitutions, bylaws, and governing documents show how organizational structure and rules evolved in response to changing circumstances and values.

Financial Records: While detailed transaction records have limited historical value, annual budgets, financial statements, and major capital campaign documentation provide important context for understanding chapter resources and priorities across time.

Correspondence Files: Letters between chapters and national headquarters, communications with university administration, and significant correspondence with alumni or community partners document relationships and institutional memory.

Membership Rosters: Comprehensive member lists including full names, initiation dates, graduation years, and positions held create essential reference tools for future researchers and provide baseline data for historical analysis.

Visual Documentation

Photographs and visual materials bring organizational history to life:

Composite Photographs: Annual fraternity composites documenting each year’s membership should be preserved comprehensively. These create visual continuity across generations and serve as primary sources for identifying members in other photographs.

Event Photography: Formal photographs from significant events—initiations (where appropriate), formals, founders’ day celebrations, philanthropic events, homecoming activities, and milestone anniversaries—document chapter traditions and social history.

Facility Documentation: Photographs showing chapter house evolution, renovations, interior spaces, and property development document physical infrastructure changes and living conditions across eras.

Historical Candid Photography: Beyond formal event images, candid photographs showing daily chapter life, study sessions, intramural sports, social gatherings, and routine activities provide authentic glimpses into member experiences.

Video and Film Archives: Historical film footage or video recordings of events, speeches, interviews, or chapter activities offer rich multimedia documentation unavailable through static photographs alone.

Publications and Printed Materials

These items document how organizations presented themselves:

Newsletters and Magazines: Chapter newsletters, alumni publications, and national organization magazines chronicle events, feature member achievements, and communicate organizational values across time periods.

Recruitment Materials: Rush brochures, information packets, and recruitment presentations show how chapters marketed themselves to prospective members and what qualities they emphasized in different eras.

Event Programs: Programs from formals, philanthropic events, founders’ day celebrations, and special occasions document specific events and participants.

Scrapbooks: Historical scrapbooks often contain eclectic collections of programs, photographs, newspaper clippings, and ephemera that provide rich contextual details about specific time periods.

Artifacts and Memorabilia

Physical objects connect tangibly with organizational history:

Badges and Pins: Historical membership badges, officer pins, and ceremonial jewelry represent tangible connections to specific members and eras.

Banners and Flags: Chapter banners, ceremonial flags, and award banners document achievements and create visual symbols of organizational identity.

Trophies and Awards: Intramural trophies, Greek life awards, academic recognition awards, and philanthropic honors document chapter achievements and competitive successes.

Regalia and Ceremonial Items: Historical robes, sashes, or other ceremonial items (where appropriate to preserve) represent ritual traditions.

Historical Furniture and Decor: Select pieces of historical furniture, house crests, composite frames, or decorative elements can preserve tangible connections to physical spaces and aesthetic traditions.

Oral Histories and Personal Narratives

Some of the most valuable historical information exists only in memories:

Alumni Interviews: Recorded interviews with long-time members, particularly those from significant historical periods, capture perspectives and stories that exist nowhere in written records.

Leadership Narratives: Documented accounts from chapter presidents, house corporation leaders, and other key figures provide insider perspectives on decision-making and challenges faced during their tenures.

Tradition Documentation: Many cherished chapter traditions, songs, rituals, and customs exist only in institutional memory. Recording these from knowledgeable members prevents permanent loss.

Not every item from these categories requires permanent preservation—strategic selection focusing on representative examples and materials documenting significant events or transitions creates manageable, valuable archives rather than overwhelming collections of everything ever produced.

Assessing Your Current Historical Collection

Before implementing preservation strategies, conduct comprehensive assessment of existing historical materials. This inventory process reveals what you have, identifies gaps, prioritizes preservation needs, and informs strategic planning.

Conducting a Historical Materials Inventory

Systematic inventory provides foundation for preservation planning:

Physical Location Survey: Identify all locations where historical materials exist—chapter house storage areas, alumni volunteers’ homes, national organization archives, university special collections, off-site storage units, or scattered among individual members. Many chapters discover materials in unexpected places once they begin systematic searching.

Material Categorization: As you locate items, categorize them by type (documents, photographs, artifacts, publications) and approximate era. This organizational framework guides subsequent preservation decisions.

Condition Assessment: Evaluate physical condition of materials using simple categories—excellent (no damage), good (minor wear), fair (noticeable deterioration but stable), poor (active deterioration or significant damage), or critical (immediate intervention needed to prevent loss). This assessment prioritizes preservation efforts toward most vulnerable materials.

Content Identification: Document what each item or collection contains—date ranges, subjects, individuals pictured, or events documented. This metadata makes materials useful for research and retrieval rather than simply stored boxes of unknown content.

Gap Analysis: Compare your inventory against comprehensive chapter history to identify missing periods, underrepresented eras, or types of documentation you lack. These gaps might guide targeted efforts to locate additional materials or conduct oral histories filling informational voids.

Prioritizing Materials for Preservation

With comprehensive inventory complete, establish priorities for preservation efforts:

Irreplaceability: Materials that exist in single copies or cannot be recreated deserve highest priority. Original founding documents, unique photographs, handwritten meeting minutes, and one-of-a-kind artifacts should be preserved before items that exist in multiple copies.

Historical Significance: Materials documenting founding periods, significant challenges or controversies, major achievements, important leadership transitions, or transformative events warrant priority over routine documentation.

Physical Vulnerability: Items in poor condition or housed in environments causing active deterioration require urgent intervention regardless of other factors. Stopping ongoing damage prevents complete loss.

Research Value: Materials containing rich information useful for understanding organizational evolution, member experiences, or historical context provide greater long-term value than items offering minimal informational content.

Member Interest: Materials likely to engage current members and alumni—particularly photographs and documentation from recent decades—may warrant priority because they support active engagement alongside historical preservation.

Prioritization ensures limited time and resources address most critical preservation needs first while creating systematic plans for comprehensively addressing entire collections over time.

Engaging Knowledgeable Alumni

Alumni with institutional memory provide invaluable assistance during inventory and assessment:

Identification Assistance: Long-time members can identify individuals in unlabeled photographs, provide context for undocumented events, clarify cryptic references in historical documents, and explain traditions whose meanings have been lost.

Additional Material Location: Knowledgeable alumni often know about materials in private possession, organizational records stored in unexpected locations, or historical information sources current members don’t realize exist.

Historical Context: Alumni who lived through significant periods can explain why certain decisions were made, what challenges chapters faced, how traditions evolved, and what events meant to members at the time—context that transforms raw materials into meaningful historical narratives.

Preservation Advocacy: Engaging respected alumni in inventory and assessment processes creates preservation champions who can advocate for funding, volunteer their time, and encourage broader alumni support for heritage conservation efforts.

Conducting thorough assessment provides clear understanding of preservation challenges and opportunities while building foundation for strategic intervention.

Physical Preservation Methods for Documents and Photographs

Once you’ve identified and prioritized materials requiring preservation, implementing appropriate conservation methods protects them from further deterioration while maintaining accessibility.

Environmental Controls for Storage

Proper environmental conditions dramatically extend material lifespan:

Temperature Stability: Store historical materials in climate-controlled environments maintaining 65-70°F year-round. Avoid attics with extreme summer heat, unheated basements, or other spaces experiencing significant temperature fluctuations that accelerate deterioration.

Humidity Management: Relative humidity between 30-50% prevents mold growth (thrives above 60% humidity) while avoiding brittleness caused by excessive dryness. Avoid damp basements, humid attics, or spaces lacking environmental controls.

Light Protection: Minimize light exposure, particularly sunlight and fluorescent lighting containing damaging ultraviolet radiation. Store materials in closed boxes, use UV-filtering covers on fluorescent fixtures, and never display original documents or photographs in direct sunlight.

Air Quality: Avoid storage in areas with chemical fumes, excessive dust, or air pollution. Basements with oil furnaces, areas near automotive facilities, or dusty attics pose risks to historical materials.

Pest Prevention: Ensure storage areas are secured against insects and rodents that damage paper and fabric materials. Regular inspections and proper facility maintenance prevent pest-related losses.

For chapters lacking climate-controlled storage space, consider partnering with university archives, renting appropriate off-site storage, or working with alumni volunteers who can provide suitable home storage environments.

Proper Housing and Containers

How materials are stored significantly affects their preservation:

Archival-Quality Boxes and Folders: Use acid-free, lignin-free storage boxes and folders specifically manufactured for archival preservation. Standard cardboard boxes contain acids that migrate to documents, causing deterioration. Archival suppliers provide appropriate materials at reasonable costs.

Photograph Storage: Store photographs in archival-quality albums, sleeves, or boxes. Never use “magnetic” photo albums or standard plastic sleeves, which often contain polyvinyl chloride (PVC) that damages photographs. Archival polyester, polypropylene, or polyethylene sleeves provide safe photograph protection.

Large Format Materials: Oversized items like composite photographs, banners, or architectural drawings should be stored flat rather than rolled when possible. If flat storage is impractical, roll items around acid-free tubes with acid-free tissue paper protection.

Separation of Material Types: Store different material types separately—photographs separate from documents, acidic newspaper clippings isolated from other materials, artifacts stored separately from paper materials. This prevents chemical interactions that cause damage.

Labeling and Organization: Label all storage containers clearly with contents and date ranges. Organizational systems using consistent labels and logical arrangement make materials findable rather than simply stored.

Handling Protocols

Proper handling prevents unnecessary damage to historical materials:

Clean Hands: Always handle materials with clean, dry hands or wear cotton gloves when handling particularly fragile or valuable items. Oil and dirt from skin transfer to materials, causing long-term damage.

Supportive Handling: Support fragile documents fully rather than handling by corners or edges. Use both hands when moving bound volumes, and never force materials to lie flat if bindings are tight.

Work Surface Preparation: Examine materials on clean, clear work surfaces with adequate space. Never eat or drink around historical materials.

Limited Handling: Minimize handling of original materials. Once digitized, refer to digital copies for regular use rather than repeatedly handling originals.

Damage Documentation: When discovering damaged materials, document damage photographically before attempting intervention. Some types of damage require professional conservation rather than well-meaning amateur attempts that worsen problems.

Conservation Treatments

Some materials require professional conservation intervention:

Professional Assessment: Consult professional conservators for materials showing active deterioration, significant damage, or exceptional historical value. University libraries often provide conservation consultation even for private collections.

Appropriate Interventions: Professional conservators can stabilize deteriorating materials, remove damaging adhesives and fasteners, repair tears, deacidify paper, and implement other treatments beyond amateur capability.

When to Intervene: Seek professional conservation for materials showing mold growth, insect damage, severe brittleness, water damage, or deterioration threatening material survival. Don’t attempt amateur conservation of valuable or severely damaged items.

Preventive vs. Restorative: Focus resources primarily on preventive conservation—proper storage, environmental controls, appropriate handling—rather than expensive restorative treatments. Prevention costs far less than intervention while providing better long-term results.

Specialized Materials Considerations

Different material types require specific approaches:

Newspaper Clippings: Newspapers printed on acidic paper deteriorate rapidly. Photocopy clippings onto acid-free paper for long-term preservation, and consider discarding deteriorating originals after digitization if they contain no unique annotations or characteristics.

Scrapbooks: Historical scrapbooks often contain items attached with damaging adhesives, acidic papers affecting adjacent items, and format challenging for preservation. Consider carefully disassembling scrapbooks for proper item-level preservation, documenting original arrangement photographically before disassembly.

Textiles and Banners: Store fabric items flat or carefully rolled around acid-free tubes with acid-free tissue paper. Keep textiles in dark, cool environments and consider periodic unfolding to prevent permanent creases.

Digital Media: Older digital formats (floppy disks, CDs, DVDs) deteriorate and use obsolete technologies. Migrate digital materials to current formats regularly and maintain multiple backup copies.

Implementing appropriate physical preservation methods protects original materials while you develop comprehensive digital archives that provide broader accessibility without ongoing handling of fragile originals.

Creating Digital Archives: Digitization Best Practices

While physical preservation protects original materials, digitization creates accessible archives that can be shared broadly without risking damage to originals. Comprehensive digital preservation also provides insurance against catastrophic loss of physical materials.

Planning Your Digitization Project

Successful digitization requires strategic planning before scanning begins:

Scope Definition: Determine what materials you’ll digitize—everything in your collection, or selected high-priority items. Complete digitization provides comprehensive access but requires more time and resources. Selective digitization addresses immediate needs while allowing phased expansion.

Quality Standards: Establish minimum resolution and file format standards ensuring digital copies serve preservation and access purposes effectively. Document scanning typically requires 300-600 DPI; photographs benefit from higher resolution (600-1200 DPI); oversized materials and artifacts may need specialized capture approaches.

Workflow Development: Create systematic workflows for preparing materials, capturing digital images, quality review, metadata creation, file organization, backup procedures, and returning original materials to storage. Documented workflows ensure consistency and efficiency, particularly when multiple people contribute to projects.

Resource Assessment: Evaluate available resources including equipment (scanners, cameras, computers, storage), personnel (volunteers, staff, students), budget for external services, and timeline constraints. Realistic resource assessment informs scope decisions and phasing strategies.

Rights and Privacy Considerations: Establish policies regarding who can access digitized materials and what information requires privacy protection. Consider member privacy, copyright issues for published materials, and appropriate access restrictions for sensitive organizational information.

Digitization Methods and Equipment

Different material types require appropriate capture approaches:

Flatbed Scanning: Standard flatbed scanners work well for documents, photographs, and other materials lying flat. Quality document scanners provide consistent results and appropriate resolution for most preservation needs.

Large Format Scanning: Oversized materials like composite photographs, architectural drawings, or banners require large-format scanners or professional scanning services. Many university libraries and commercial vendors provide large-format scanning capabilities.

Photography for Artifacts: Three-dimensional artifacts and items that cannot be placed on scanners should be photographed using quality digital cameras with appropriate lighting. Create multiple views showing different angles and details.

Bound Volume Scanning: Historical minute books and other bound volumes require specialized approaches. Book scanners or careful photography prevent damage to bindings. Never force bindings flat to fit standard scanners—this causes permanent damage.

Negative and Slide Scanning: Historical negatives and slides require specialized scanners or scanning services. These original capture formats often provide higher quality than prints made from them.

Video and Film Digitization: Historical film footage and videotapes require professional digitization services with appropriate equipment for different formats. Prioritize video and film digitization because these formats deteriorate relatively rapidly.

Metadata and Organization

Digital images without information about their content provide limited research value:

Essential Metadata: At minimum, include descriptive titles, date or date range, individuals pictured (if known), event or context, and any other identifying information helping users understand what they’re viewing.

Standardized Vocabularies: Develop consistent terminology for common subjects, events, or categories. Standardization makes searching and browsing more effective than idiosyncratic descriptions varying by whoever created them.

File Naming Conventions: Implement logical, consistent file naming that incorporates key information (date, subject, type) while being readable by both humans and computer systems. Avoid special characters, spaces, and excessively long names causing technical problems.

Searchable Systems: As digital collections grow, implement searchable database systems rather than relying solely on folder organization. Searchable metadata dramatically improves usability for large collections.

Linked Information: When materials relate to entries in other records (member rosters, event listings, etc.), create links between related items. This connectedness transforms isolated images into comprehensive historical documentation.

Digital Storage and Preservation

Digital materials require ongoing management preventing technological obsolescence and data loss:

Multiple Backup Locations: Maintain digital archives in at least three separate locations—local storage, external hard drives, and cloud storage services. Geographic separation protects against local disasters affecting all copies simultaneously.

Regular Backup Verification: Periodically verify that backups remain readable and complete. Automated backup systems fail silently; regular testing confirms protection remains effective.

File Format Considerations: Use standard, non-proprietary file formats likely to remain readable as technology evolves. TIFF or JPEG for images, PDF or TXT for documents, and standard formats for audio/video provide better long-term accessibility than proprietary formats requiring specific software.

Migration Planning: As storage technologies and file formats evolve, plan periodic migration to current systems. CDs, DVDs, and obsolete cloud services eventually become unreadable; proactive migration prevents loss.

Documentation Preservation: Maintain documentation about digitization standards, equipment used, file organization systems, and workflow processes. This information helps future archivists understand and manage inherited digital collections.

Outsourcing vs. In-House Digitization

Chapters must decide whether to digitize materials themselves or engage professional services:

Professional Services: Commercial digitization companies and university library services provide high-quality results, appropriate equipment for all material types, and expertise handling fragile materials. Professional services cost more but deliver faster results with consistent quality and without requiring volunteer time.

In-House Projects: Volunteer-based digitization saves money and creates meaningful engagement opportunities for alumni and members interested in organizational history. Success requires appropriate equipment, trained volunteers, quality control processes, and realistic timeline expectations.

Hybrid Approaches: Many chapters use hybrid strategies—outsourcing complex, fragile, or high-priority materials while handling straightforward digitization internally. This balances cost, quality, and engagement considerations.

Creating comprehensive digital archives makes fraternity and sorority history accessible to members and alumni regardless of geographic location while providing insurance protecting against physical material loss.

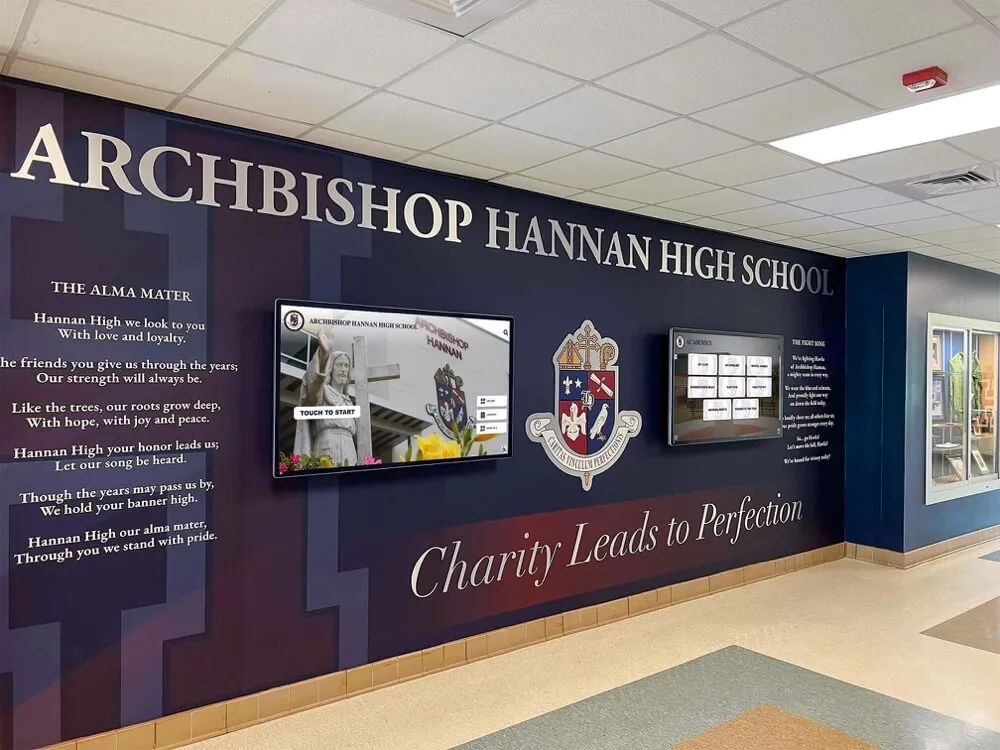

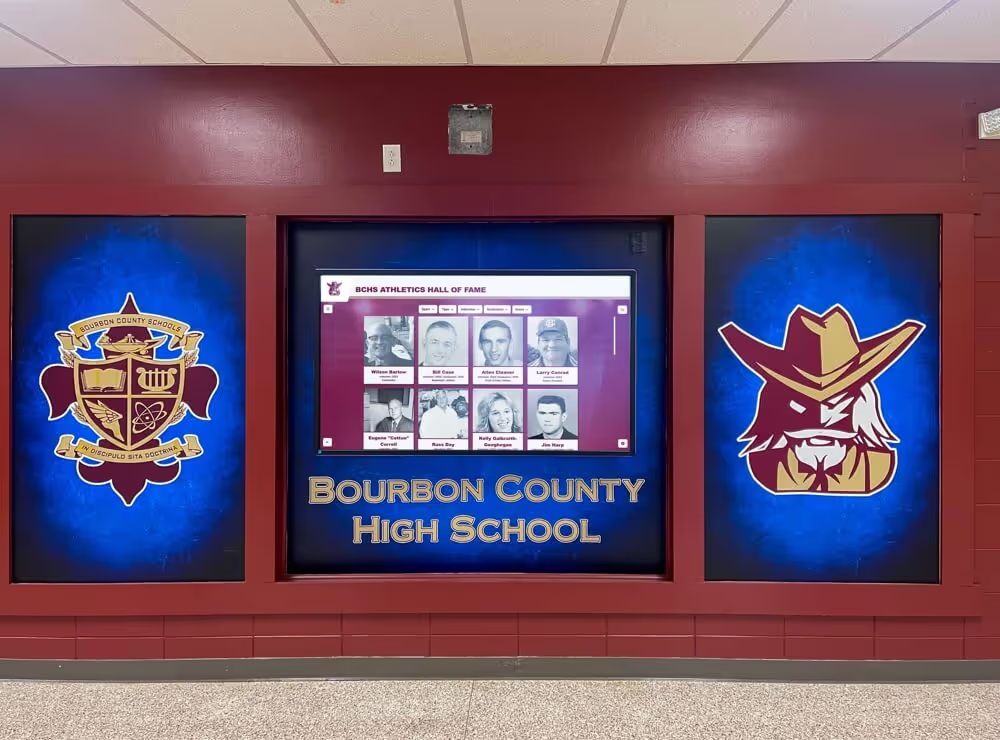

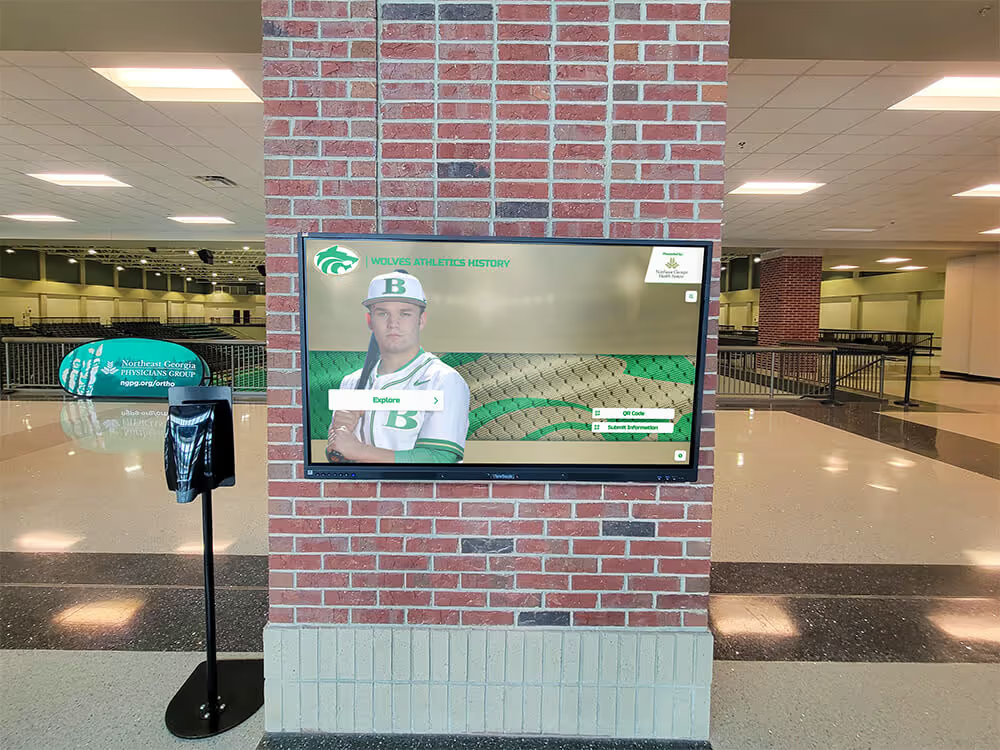

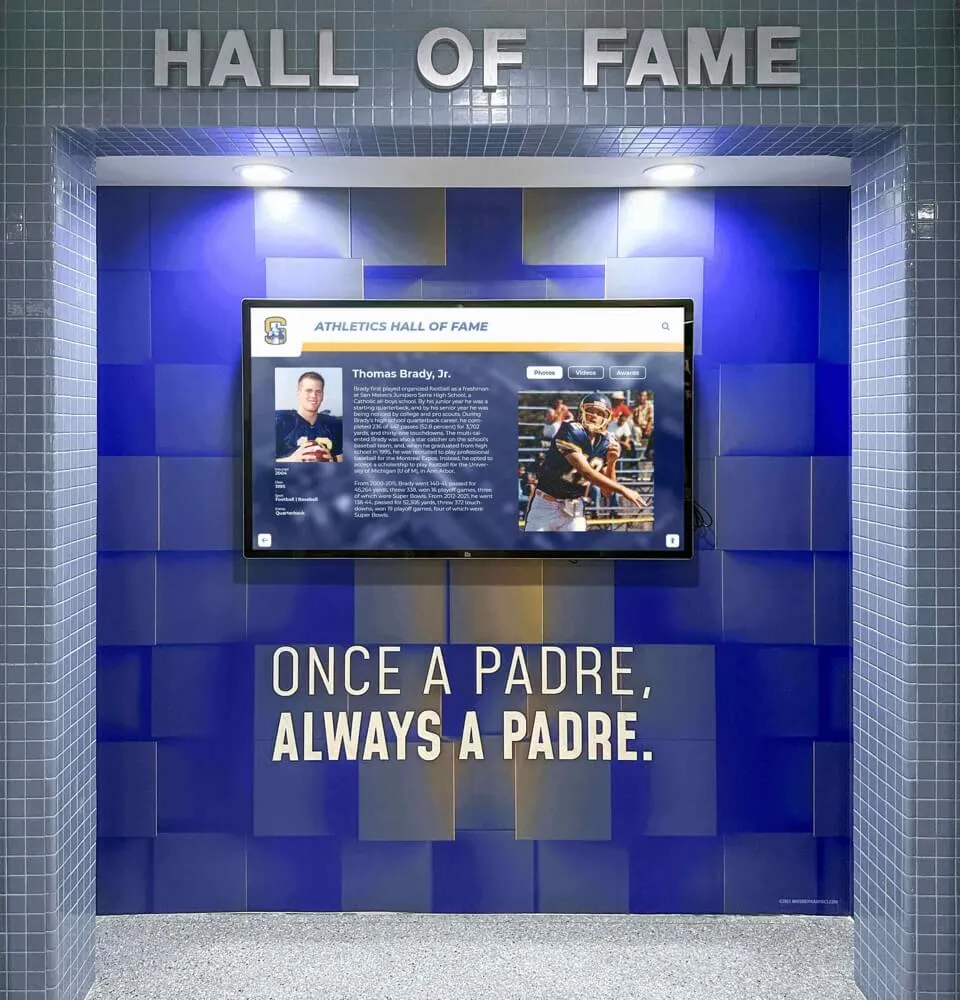

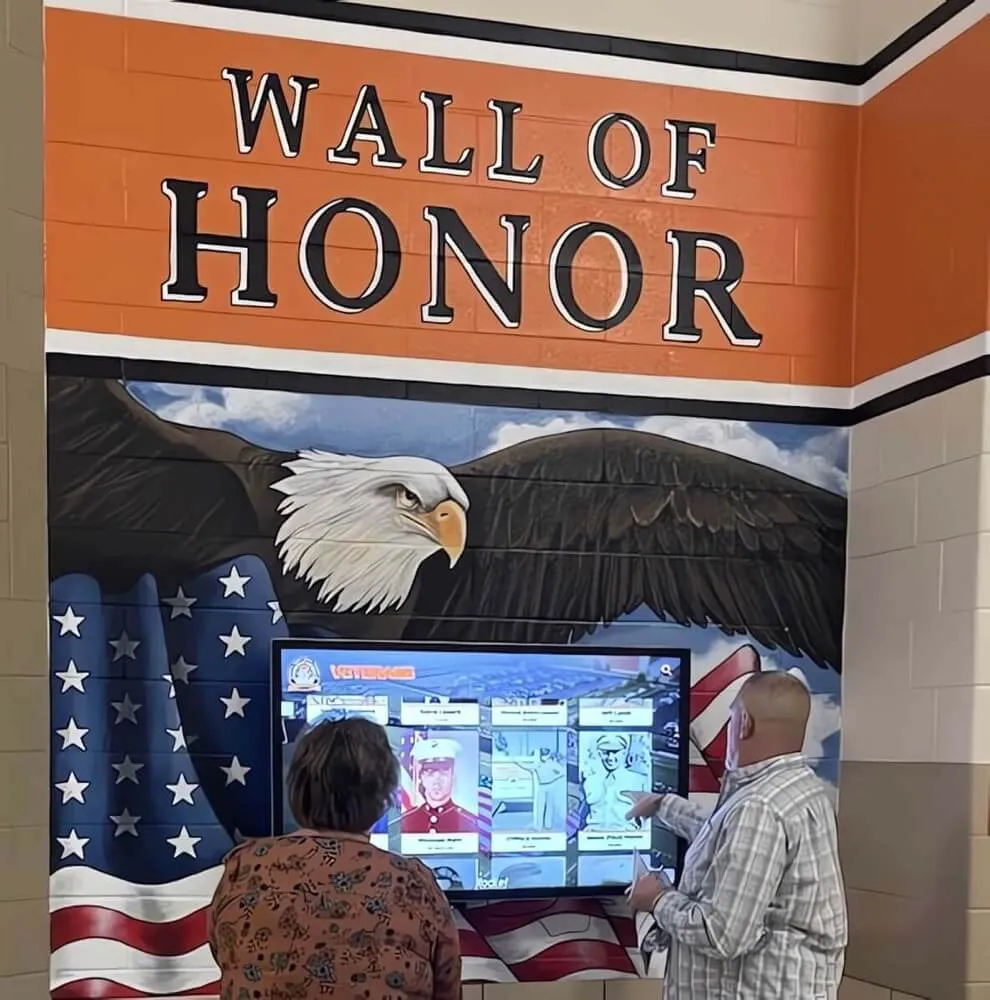

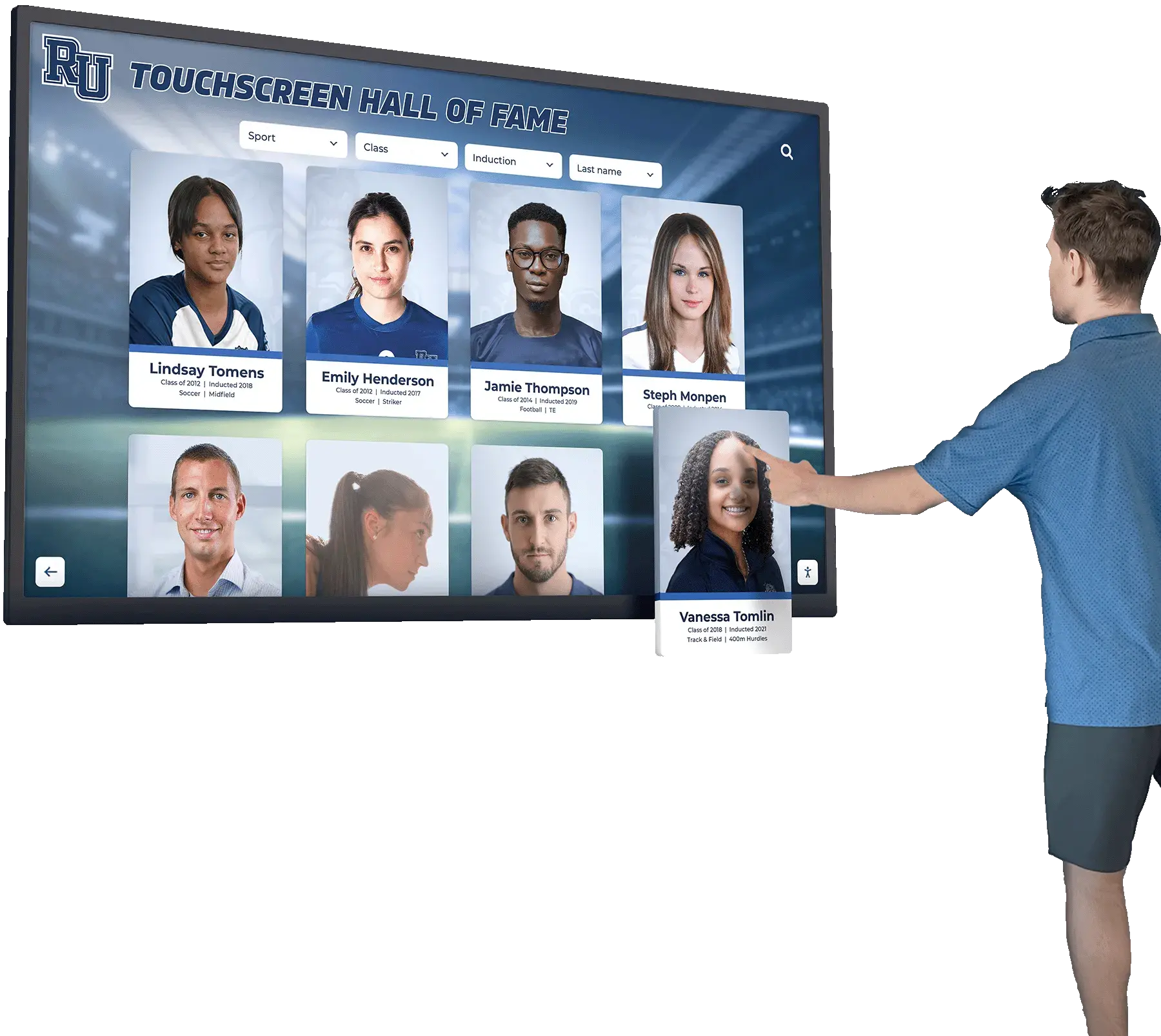

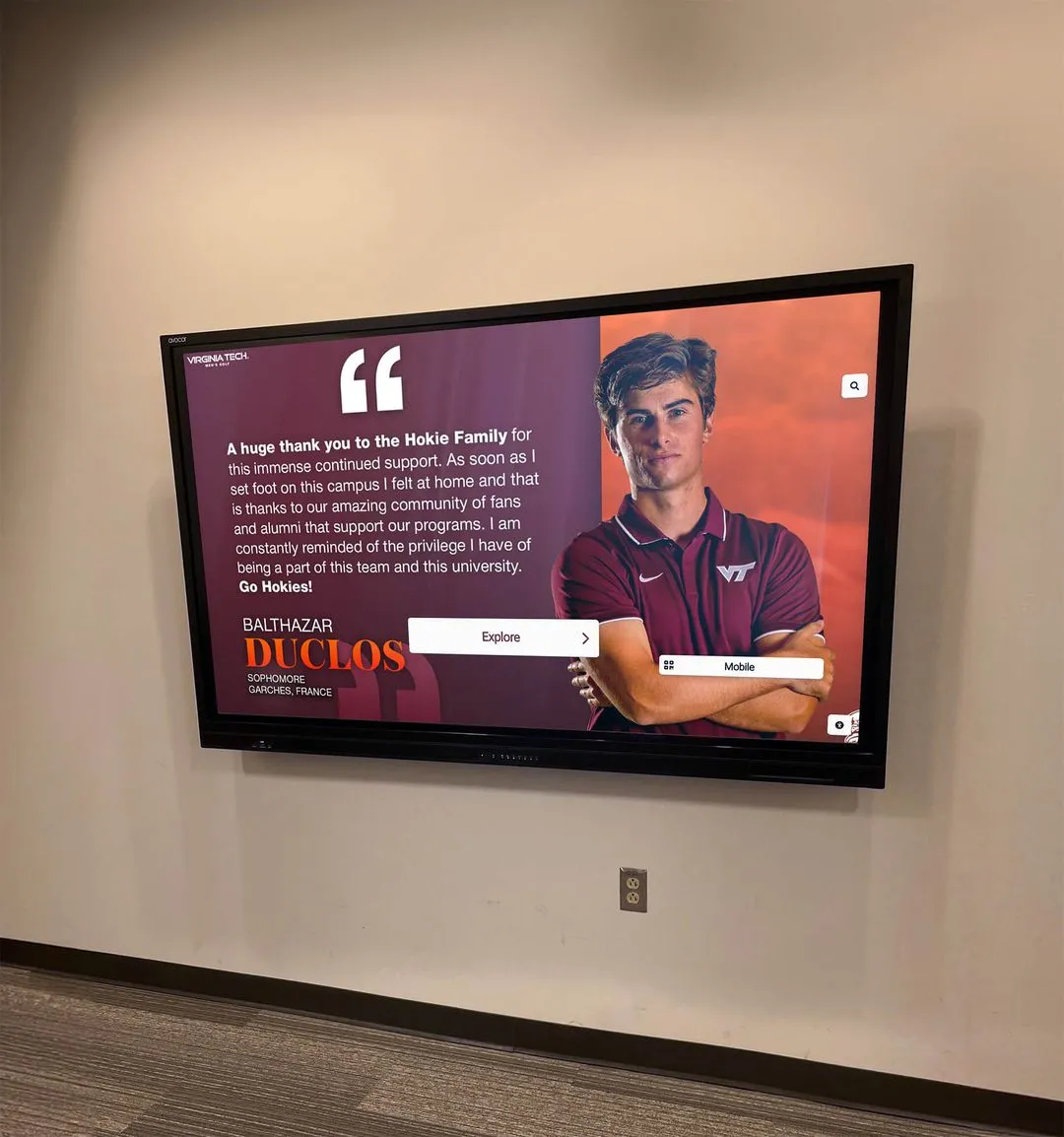

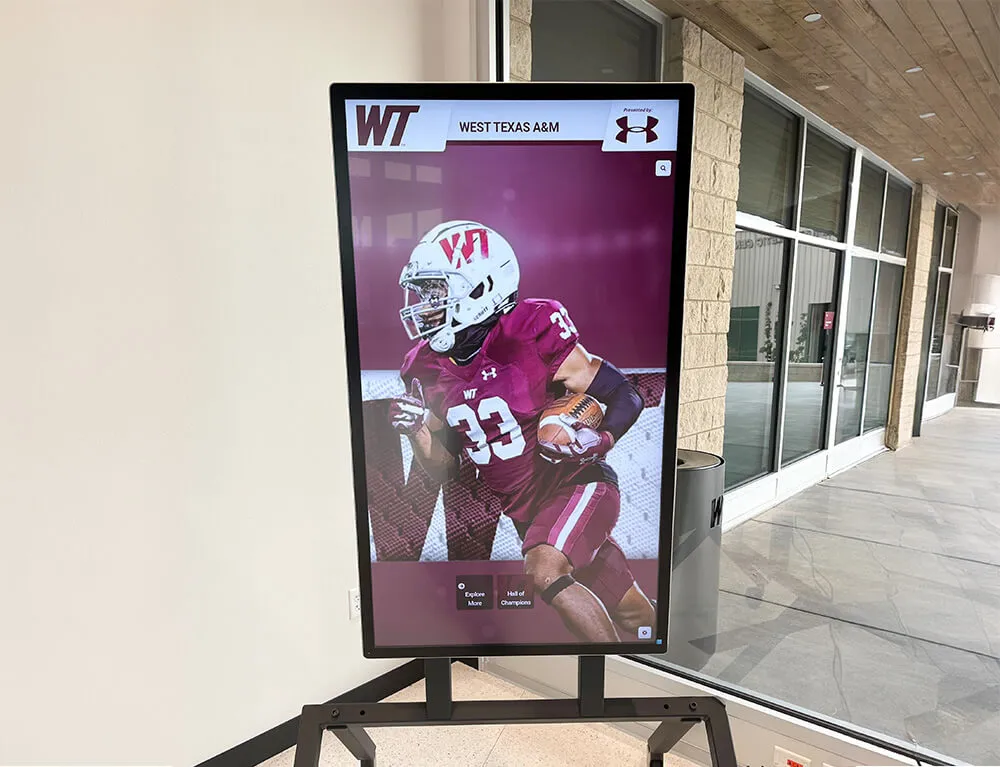

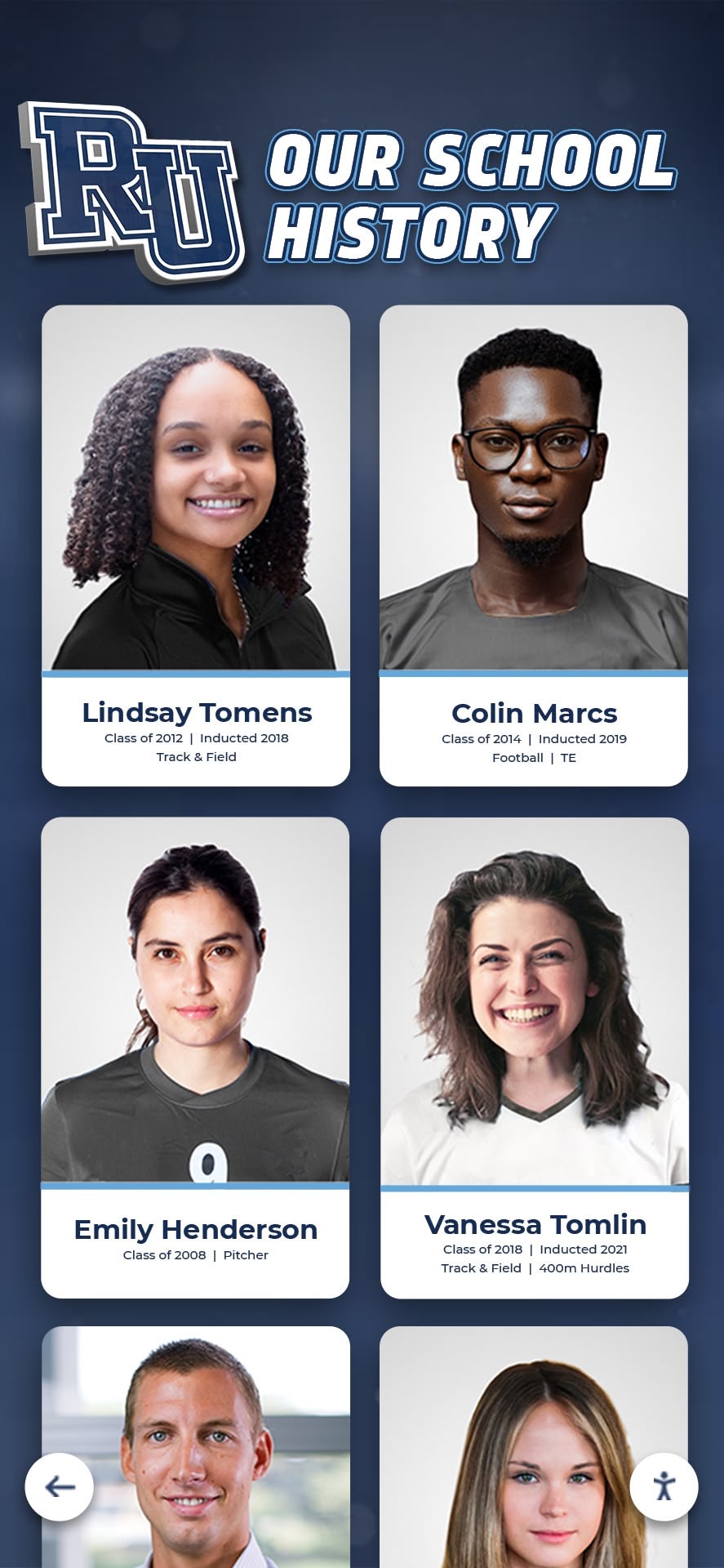

Implementing Interactive Digital Recognition Systems

Beyond creating static digital archives, modern technology enables interactive digital recognition systems that transform historical materials into engaging experiences for current members, visitors, and alumni.

Benefits of Interactive Historical Displays

Interactive systems provide advantages beyond traditional archives:

Enhanced Engagement: Touchscreen interfaces invite exploration rather than passive viewing. Visitors spend significantly more time with interactive historical content than reading static displays or browsing traditional scrapbooks.

Unlimited Capacity: Digital systems accommodate entire chapter histories without physical space constraints. Unlike wall space limited to displaying recent composites or selected historical items, digital platforms can showcase centuries of organizational history simultaneously.

Searchable Databases: Interactive systems allow visitors to search for specific members, years, events, or achievements rather than browsing chronologically. This findability dramatically increases practical utility, particularly for alumni seeking their own years or researching specific information.

Multimedia Integration: Digital platforms incorporate photographs, documents, video, audio recordings, and linked information creating rich historical narratives impossible through single-medium presentations.

Remote Accessibility: Web-accessible platforms extend historical access to alumni unable to visit chapter houses physically. Geographic barriers no longer prevent engagement with organizational heritage.

Easy Updates: Digital systems allow continuous content additions and corrections without physical reinstallation or reproduction costs. Historical collections grow and improve over time as new materials are discovered or contributed.

Core Features for Fraternity and Sorority Historical Systems

Effective historical recognition platforms include specific capabilities:

Chronological Organization: Allow users to browse history by decade, year, or specific date ranges. Chronological navigation provides intuitive structure for exploring organizational evolution over time.

Member Profiles: Individual member profiles connecting photographs from composites, biographical information, positions held, and post-graduation accomplishments create comprehensive member recognition while supporting alumni networking.

Event Documentation: Organize content around significant events—founders’ day celebrations, philanthropic initiatives, milestone anniversaries, renovations, award recognition—creating narrative structure beyond simple chronological listing.

Leadership Recognition: Highlight chapter officers, house corporation leadership, advisory board members, and alumni volunteers whose service sustained organizations across generations.

Achievement Celebration: Feature academic honors, athletic accomplishments, Greek life awards, philanthropic milestones, and other achievements demonstrating organizational values and member success.

Tradition Documentation: Explain chapter traditions, ceremonial practices (where appropriate), songs, mottos, and customs that define organizational culture and identity.

Search Functionality: Robust search allowing queries by name, year, position, event, or keyword makes large historical collections practically useful rather than merely comprehensive.

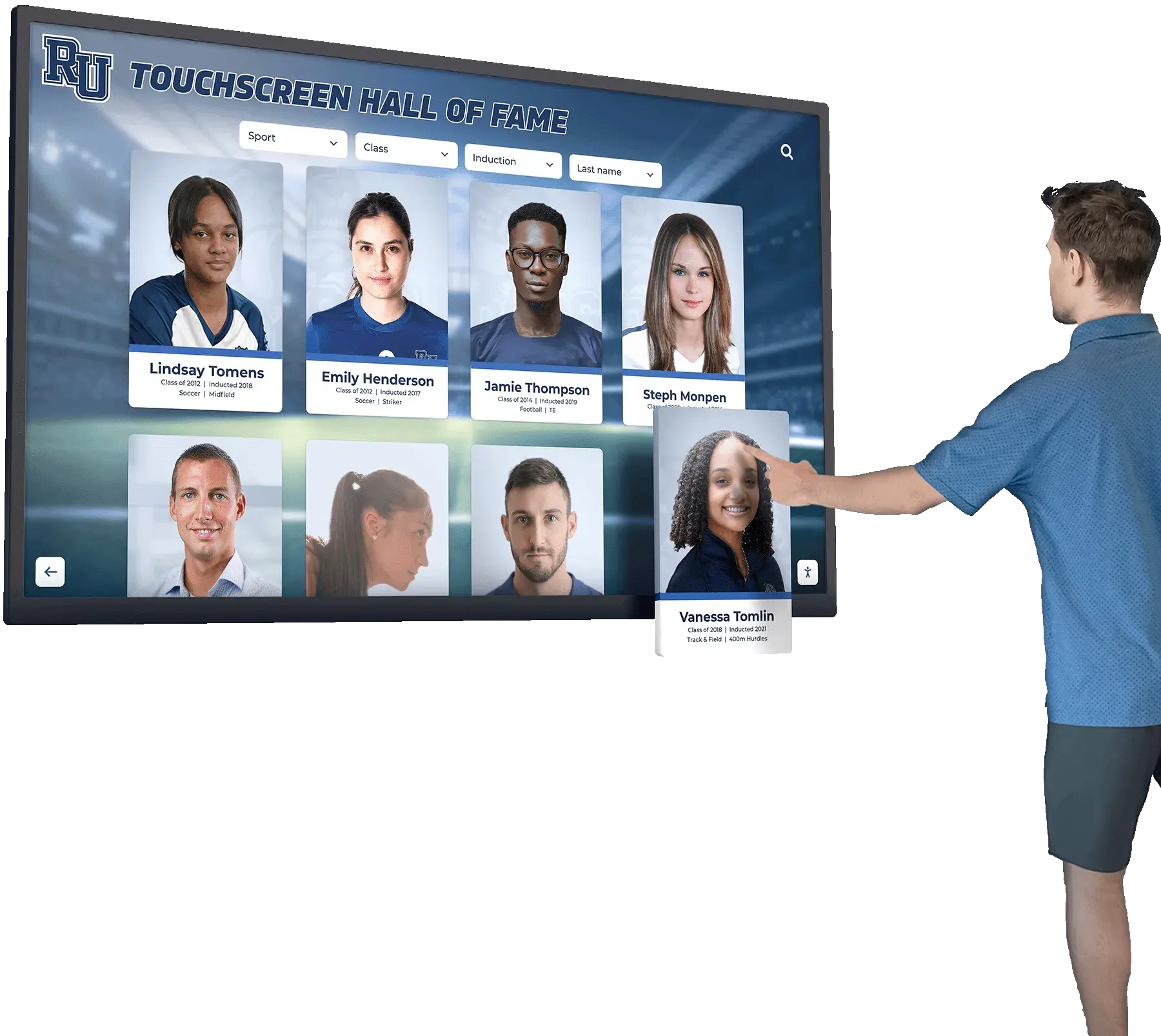

Implementation in Chapter Houses

Installing interactive historical systems in physical chapter facilities creates anchor points for member and alumni engagement:

High-Traffic Locations: Position displays in entrance halls, chapter rooms, dining areas, or other spaces where members and visitors naturally gather. Visibility encourages regular interaction rather than treating historical displays as hidden resources.

Appropriate Hardware: Commercial-grade touchscreen displays designed for extended operation provide reliability in residential environments. Size selection should balance visibility with available space—55-65 inch displays suit most chapter house applications.

Aesthetic Integration: Design displays that complement chapter house architecture and decor rather than appearing as afterthoughts. Thoughtful integration demonstrates that organizations value their history sufficiently to present it beautifully.

Durability Considerations: Chapter house environments experience heavy use during social events. Secure mounting, protective glass, and robust hardware withstand residential facility demands.

Network Connectivity: Most interactive systems require internet connectivity for content updates and cloud synchronization. Ensure adequate WiFi coverage or wired ethernet access at installation locations.

Web-Based Historical Archives

Companion websites make historical content accessible beyond physical chapter houses:

Alumni Accessibility: Geographic dispersion means most alumni cannot regularly visit chapter houses. Web accessibility maintains historical connection regardless of physical distance, supporting alumni engagement across decades and distances.

Recruitment Resources: Prospective members researching organizations online can explore comprehensive chapter histories, seeing stability, tradition, and values demonstrated through decades of documentation.

Family Connections: Parents, grandparents, and other family members can explore organizations their students are joining, building family engagement and understanding.

Research Access: Historians, journalists, or students researching Greek life history, women’s education, student culture, or related topics can access materials supporting scholarship without physical archive visits.

Mobile Optimization: Ensure web-based historical platforms function excellently on smartphones and tablets, accommodating how most users access online content.

Content Management and Sustainability

Interactive systems require ongoing content management ensuring long-term value:

Intuitive Management Tools: Platforms should provide user-friendly content management interfaces allowing chapter historians or volunteers to add materials, update information, and organize content without technical expertise.

Defined Responsibilities: Assign specific individuals—chapter historians, alumni volunteers, or house corporation representatives—clear responsibility for ongoing content management. Documented expectations prevent systems from becoming outdated.

Alumni Contribution Opportunities: Enable alumni to submit their own photographs, stories, and biographical updates. Crowdsourcing content development engages alumni while building more comprehensive collections than any single person could create.

Quality Review Processes: Implement review workflows ensuring contributed content meets quality and appropriateness standards before public display. Volunteer moderators can review submissions efficiently.

Regular Content Additions: Treat historical platforms as living resources receiving continuous additions rather than one-time projects. Annual cycles adding new composites, documenting recent events, and incorporating newly discovered historical materials maintain relevance and encourage repeated engagement.

Solutions like Rocket Alumni Solutions provide comprehensive platforms specifically designed for organizational recognition and historical preservation, combining intuitive content management, interactive touchscreen displays, web accessibility, and ongoing support that makes sustainable historical preservation practical for Greek organizations.

Documenting Oral Histories and Institutional Memory

While documents, photographs, and artifacts preserve tangible historical evidence, some of the most valuable historical information exists only in memories of long-time members. Systematic oral history projects capture these perspectives before they’re permanently lost.

Why Oral Histories Matter

Recorded interviews provide unique historical value:

Context and Interpretation: Documents record what happened; oral histories explain why decisions were made, what challenges existed, how members felt, and what events meant to participants—context that transforms raw facts into meaningful narratives.

Undocumented Information: Many significant events, daily routines, interpersonal dynamics, and traditions never appear in official records. Alumni memories often provide only available documentation of important aspects of chapter life.

Multiple Perspectives: Different members experienced the same periods from varied viewpoints. Collecting diverse oral histories creates nuanced understanding rather than single-voice narratives.

Personal Connection: Hearing alumni voices discussing their experiences creates emotional connections that written histories cannot replicate. Future generations encounter predecessors as real people rather than names in records.

Tradition Preservation: Many cherished chapter traditions, songs, rituals, and customs exist only in institutional memory. Recording these from knowledgeable sources prevents permanent loss.

Identifying Interview Candidates

Strategic selection identifies alumni with most valuable historical knowledge:

Long-Tenured Members: Alumni who were active during significant periods—founding, major challenges, facility acquisitions, organizational controversies, or transformative successes—provide insider perspectives on pivotal moments.

Leadership Alumni: Former chapter presidents, house corporation officers, advisory board members, and long-serving volunteers understand organizational operations and decision-making processes that shaped chapter evolution.

Diverse Perspectives: Seek interviewees representing different eras, demographic backgrounds, and positions within the organization. Diversity prevents single perspective from dominating historical narrative.

Knowledgeable Historians: Some alumni develop deep knowledge of chapter history through personal interest, service as historians, or long association with the organization. These individuals can provide broad historical overviews and identify other valuable interview candidates.

Time Sensitivity: Prioritize oldest alumni and those in declining health. Once these individuals pass away, their unique perspectives and memories disappear permanently.

Conducting Effective Oral History Interviews

Thoughtful interview approaches yield richer historical documentation:

Preparation and Research: Before interviews, research the interviewee’s tenure, review relevant historical documents, and develop specific questions addressing gaps in existing documentation. Informed interviewers ask better questions and recognize valuable information when they hear it.

Question Strategies: Use open-ended questions encouraging storytelling rather than yes/no questions generating minimal information. Ask about specific events, daily routines, relationships, challenges faced, and how things changed over time.

Follow-Up and Clarification: When interviewees mention intriguing details, ask follow-up questions exploring topics more deeply rather than rigidly following prepared scripts. Some of the most valuable information emerges through conversational exploration.

Recording Quality: Use quality recording equipment ensuring clear audio. Position microphones appropriately, test equipment before interviews, monitor recording during sessions, and create backup recordings when possible. Poor audio quality can render interviews unusable.

Video Consideration: Video recording captures facial expressions, gestures, and visual context adding richness beyond audio-only interviews. However, video requires more technical setup and some interviewees feel more comfortable with audio-only recording.

Interview Length: Plan 60-90 minute sessions for most interviews. Longer sessions risk participant fatigue reducing information quality; shorter sessions may miss important information.

Comfortable Settings: Conduct interviews in locations where participants feel comfortable—their homes, chapter houses, or familiar campus locations. Relaxed interviewees provide more thoughtful, detailed responses.

Processing and Preserving Oral Histories

Recorded interviews require post-production work maximizing their historical value:

Transcription: Create written transcripts of interviews. While transcription requires significant time, written versions make information searchable and accessible to users preferring reading over listening. Many affordable transcription services now use AI-assisted approaches reducing costs.

Metadata Documentation: Record comprehensive information about each interview—participant names, interview date and location, interviewer names, topics covered, and significant themes discussed. Detailed metadata makes collections searchable and usable.

Indexing: For longer interviews, create time-stamped indexes noting when specific topics are discussed. Indexes allow users to navigate directly to relevant segments rather than listening to complete recordings searching for particular information.

Rights and Permissions: Obtain signed releases from interviewees granting permission for archival preservation and specified uses. Clarify any restrictions on access, quotation, or reproduction the interviewee requests.

Digital Preservation: Store audio/video files using standard formats in multiple locations with regular backups, applying same digital preservation principles used for other materials.

Integration with Archives: Connect oral histories with related materials in your archives—mention relevant documents, photographs, or events; cross-reference transcripts with visual materials; create links allowing users to explore related content.

Making Oral Histories Accessible

Recorded interviews provide maximum value when easily accessible:

Online Access: Make oral history recordings and transcripts available through web-based platforms allowing alumni and researchers to access materials remotely.

Featured Excerpts: Highlight particularly interesting or significant oral history segments in newsletters, social media, or anniversary publications, drawing attention to larger collections.

Interactive Display Integration: Incorporate audio or video clips from oral histories into touchscreen historical displays, adding multimedia richness to visual content.

Research Support: Make oral history collections discoverable through institutional archives, special collections, or research databases supporting scholarly access.

Systematic oral history programs capture irreplaceable perspectives and stories that enrich organizational archives far beyond what documents and photographs alone can provide.

Establishing Sustainable Record-Keeping Systems

Beyond preserving historical materials, forward-thinking organizations implement systematic approaches ensuring current activities are documented appropriately for future historians. Establishing sustainable record-keeping prevents today’s chapter life from becoming tomorrow’s historical gaps.

Creating Comprehensive Documentation Practices

Current documentation becomes future history:

Consistent Meeting Minutes: Maintain detailed meeting minutes documenting discussions, decisions, and actions. Well-written minutes preserved consistently create comprehensive organizational records tracking chapter evolution, leadership decisions, and member activities across decades.

Digital Photography Protocols: Document all significant events through quality digital photography. Assign photography responsibilities to specific individuals, establish minimum quality standards, and implement backup procedures ensuring images aren’t lost when photographers’ devices fail or when they graduate.

Event Documentation Templates: Create standardized templates for documenting recurring events—formals, philanthropic events, initiation ceremonies (where appropriate), awards ceremonies, facility improvements. Consistent documentation formats create more complete, comparable historical records than ad-hoc approaches.

Membership Records: Maintain comprehensive, accurate membership databases including full names, initiation dates, graduation years, positions held, contact information, and other relevant details. Digital member databases create foundation for future historical research and alumni engagement.

Financial Documentation: Preserve annual budgets, financial statements, audit reports, and documentation of major financial decisions. Financial records provide important context for understanding organizational priorities and resource allocation across time.

Correspondence Files: Maintain organized files of significant correspondence with national organizations, university administration, alumni, and external partners. Important communications document relationships and institutional memory.

Implementing Digital Asset Management

Systematic digital organization prevents accumulation of disorganized files becoming future archival nightmares:

Centralized Storage: Use shared cloud storage systems (Google Drive, Dropbox, Box, etc.) providing centralized, backed-up storage rather than distributing files across individual members’ devices. Centralization prevents material loss when members graduate or change computers.

Folder Organization: Implement logical folder structures organized by year and category. Consistent organization makes materials findable rather than merely stored.

File Naming Conventions: Establish clear file naming standards including dates, event names, and descriptive information. Consistent naming conventions make files searchable and identifiable years later when original context is forgotten.

Metadata Standards: When platforms support metadata (tags, descriptions, dates), use these features consistently. Rich metadata dramatically improves long-term discoverability.

Regular Backups: Implement automated backup systems ensuring digital files exist in multiple locations. Cloud storage provides one backup layer; maintain additional backups on external drives or alternative cloud services.

Access Management: Control access to organizational files appropriately. Current officers and historians need active access; graduated members should retain read access allowing them to contribute historical knowledge without ability to accidentally delete materials.

Historian Position Development

Effective chapter historians are central to sustainable preservation:

Clear Position Descriptions: Document historian responsibilities explicitly in chapter bylaws or position descriptions. Clarity prevents historical documentation from being neglected when other priorities compete for attention.

Training and Transition: Develop comprehensive training materials for incoming historians explaining documentation practices, archival systems, and preservation priorities. Smooth transitions prevent knowledge loss during annual officer changes.

Time and Resource Allocation: Provide historians adequate time and resources for documentation work. When historian positions are treated as honorary titles without real responsibilities or support, documentation suffers.

National Organization Resources: Many national fraternities and sororities provide historian resources, training programs, or awards recognizing excellent historical documentation. Connect chapter historians with these national resources.

Recognition and Appreciation: Acknowledge historians’ contributions through awards, recognition events, or mentions in publications. Appreciation encourages thorough documentation work despite it often occurring behind the scenes.

Collaboration with University Archives

Partnerships with institutional archives provide professional support and long-term preservation:

Identifying Collection Opportunities: Many university special collections actively collect student organization records including Greek life materials. Inquire whether your institution’s archives are interested in chapter records.

Deposit Agreements: Formal agreements depositing organizational records with university archives ensure professional preservation and access while typically allowing organizations to retain ownership and specify access restrictions.

Dual Custody Approaches: Some chapters maintain working copies of recent records while depositing older historical materials with university archives, combining accessibility for current use with professional long-term preservation.

Digitization Support: University libraries often provide digitization services, equipment access, or technical consultation supporting chapter preservation projects even when formal collection relationships don’t exist.

Research Access: Materials in university special collections become accessible to researchers, authors, and students studying Greek life history, student culture, or related topics, ensuring your organization’s history contributes to broader scholarship.

Systematic current documentation practices ensure that today’s chapter activities are recorded appropriately, preventing future historians from facing the same gaps and challenges that make older periods difficult to document comprehensively.

Engaging Members and Alumni in Preservation Efforts

Successful preservation programs require broader engagement beyond individual historians or archivists. Creating cultures that value organizational heritage ensures sustainable stewardship across leadership transitions and generations.

Building Preservation Awareness

Members and alumni must understand why historical preservation matters:

Educational Programming: Incorporate chapter history into new member education, emphasizing how your organization’s story connects to broader Greek life history, institutional development, and student culture evolution. Understanding historical context creates appreciation motivating preservation efforts.

Anniversary Celebrations: Milestone anniversaries—chapter founding, facility acquisition, national organization founding—provide natural opportunities to highlight historical materials and discuss heritage conservation importance.

Historical Displays: Visible historical recognition—whether traditional displays or interactive digital systems—remind members daily that their chapter values its past and maintains connections to generations of predecessors.

Alumni Speaker Programs: Invite long-time alumni to share their experiences and perspectives with current members. Direct connection to living history creates more powerful engagement than reading historical documents alone.

Social Media Historical Features: Regular “throwback” social media posts featuring historical photographs, stories, or facts build ongoing historical awareness while engaging alumni who enjoy reminiscing about their eras.

Creating Volunteer Opportunities

Preservation projects provide meaningful engagement opportunities for members and alumni:

Digitization Volunteers: Scanning, photographing, and processing historical materials creates hands-on projects suitable for volunteers with varying time commitments. Digitization work can accommodate individuals contributing a few hours or leading comprehensive projects.

Identification Projects: Organizing volunteer sessions where knowledgeable alumni help identify individuals in unlabeled photographs, provide context for historical events, or explain traditions turns preservation work into social events reconnecting alumni with organizational history.

Oral History Interviewers: Training members or younger alumni to conduct oral history interviews with long-time members creates intergenerational connections while developing interviewing and documentation skills.

Content Development: Writing historical narratives, creating event descriptions, or developing biographical profiles for interactive displays provides creative opportunities for volunteers who enjoy research and writing.

Transcription Teams: Volunteer transcribers can convert oral history recordings or historical handwritten documents into searchable text, breaking large projects into manageable individual tasks.

Technical Support: Alumni with technical expertise can assist with equipment setup, digital file organization, website development, or platform management, contributing specialized skills to preservation efforts.

Fundraising for Preservation Projects

Major preservation initiatives often require funding beyond regular chapter budgets:

Dedicated Preservation Campaigns: Specific fundraising campaigns for digitization projects, interactive display systems, or archival supplies allow alumni to contribute to tangible historical stewardship without competing with other fundraising priorities.

Anniversary Appeals: Milestone anniversaries create natural occasions for historical preservation fundraising, connecting contributions to celebrating organizational heritage.

Memorial Opportunities: Allowing alumni to make memorial contributions supporting preservation efforts provides meaningful ways to honor deceased members while benefiting the organization.

Grant Applications: Some foundations, Greek life organizations, and historical societies provide grants supporting preservation projects. Research potential grant opportunities and prepare competitive applications.

Matching Campaigns: Matching gift challenges where major donors agree to match contributed amounts up to specified limits often motivate broader participation, leveraging large gifts to generate additional support.

Phased Funding: Breaking large preservation projects into phases allows fundraising for manageable increments rather than requiring enormous single contributions, making projects financially feasible.

Recognition for Preservation Contributions

Acknowledging contributions reinforces preservation values:

Volunteer Recognition: Publicly thank volunteers contributing to preservation projects through newsletters, social media, recognition events, or mentions in historical displays they helped create.

Donor Acknowledgment: Recognize financial contributors through appropriate methods—donor listings, dedication opportunities, or featured mentions in materials their gifts funded.

Awards and Honors: Create chapter awards recognizing exceptional historical documentation, successful preservation projects, or sustained archival stewardship. Formal recognition demonstrates organizational commitment to heritage conservation.

Naming Opportunities: For major digital systems or comprehensive digitization projects, offering naming opportunities in honor or memory of significant alumni connects major gifts with lasting legacy.

Building cultures that value organizational history creates sustainable preservation ecosystems extending far beyond any individual historian’s tenure or isolated preservation project.

Leveraging Preserved History for Current Benefits

While preservation protects the past, comprehensive historical archives provide tangible present-day benefits that justify investments in heritage conservation.

Supporting Alumni Engagement and Fundraising

Well-maintained historical archives strengthen alumni relationships:

Emotional Connections: Alumni who see their years documented and preserved feel valued by organizations that remember them. Recognition creates emotional bonds translating into sustained engagement and support.

Networking Facilitation: Comprehensive member databases help alumni discover brothers or sisters who are fellow professionals in their industries, live in their geographic areas, or share other connections. Networking value provides practical benefit encouraging ongoing relationship.

Reunion Support: Historical materials provide natural conversation starters during reunion events. Alumni enjoy exploring their years, reminiscing about people and events, and sharing stories with classmates and current members.

Fundraising Context: When requesting donations, demonstrating organizational stewardship through well-maintained historical archives shows alumni that their chapters value tradition and manage resources responsibly—factors influencing philanthropic decisions.

Legacy Giving Programs: Comprehensive historical documentation enables development of legacy giving programs where alumni ensure their families understand organizational significance and historical context supporting estate planning decisions.

Enhancing Recruitment and Member Education

Historical resources support membership development:

Recruitment Tools: During recruitment, comprehensive historical displays demonstrate organizational stability, tradition, and values to prospective members. Depth of documented history distinguishes established organizations from newer groups.

Values Education: Historical examples of members living organizational values provide more compelling education than abstract principles alone. Stories of alumni community service, academic excellence, or leadership development illustrate values in action.

Tradition Transmission: Well-documented history ensures chapter traditions, songs, customs, and practices are transmitted consistently rather than gradually distorted or forgotten across generations.

Identity Development: Understanding organizational history helps new members develop identity connection to something larger than their immediate friend groups, creating deeper commitment to chapter values and success.

Leadership Examples: Historical documentation of previous leaders facing challenges, making difficult decisions, and guiding chapters through adversity provides inspiration and lessons for current officers navigating similar situations.

Institutional Relationships and Campus Recognition

Historical resources strengthen relationships with universities and national organizations:

Campus Legitimacy: Universities value student organizations demonstrating institutional stability, responsible stewardship, and connection to campus history. Well-preserved archives provide tangible evidence of these qualities.

Anniversary Recognitions: Milestone anniversaries create opportunities for university recognition—campus newspaper features, administration acknowledgments, or campus event participation—raising chapter profiles positively.

National Organization Relationships: National fraternities and sororities appreciate chapters maintaining organizational history and participating in broader heritage preservation. Strong historical documentation supports national award nominations and recognition programs.

Research Contributions: Making historical materials available to researchers studying Greek life, student culture, women’s education, or related topics positions organizations as contributors to scholarly understanding rather than subjects of criticism.

Community Connections: Local community organizations, historical societies, and preservation groups sometimes recognize organizations maintaining strong historical documentation, creating positive community relationships.

Crisis Management and Institutional Memory

Historical documentation provides practical benefit during challenges:

Precedent Understanding: When facing difficult decisions, accessing historical records showing how previous leaders handled similar situations provides valuable precedent and perspective.

Continuity During Transitions: Comprehensive documentation prevents institutional knowledge loss during problematic leadership transitions or membership disruptions, ensuring chapters can maintain operations despite challenges.

Legal and Administrative Documentation: Historical records sometimes provide necessary documentation for legal matters, property issues, alumni disputes, or administrative questions requiring historical verification.

Recovery After Disruption: Chapters experiencing suspension, housing loss, or other disruptions can use documented history to demonstrate their heritage and values when seeking reinstatement or rebuilding.

Strategic historical preservation creates tangible present benefits alongside protecting past heritage—a dual value proposition justifying preservation investments through both retrospective and prospective returns.

Addressing Common Preservation Challenges

Even well-intentioned preservation efforts encounter predictable obstacles. Proactive strategies address these challenges before they derail preservation programs.

Limited Resources and Competing Priorities

Greek organizations face numerous demands on limited resources:

Phased Implementation: Rather than attempting comprehensive preservation immediately, implement projects in manageable phases spread across multiple years. Gradual progress proves more sustainable than ambitious projects overwhelming available resources.

Volunteer Leverage: Maximize volunteer contributions from members, alumni, and supporters to extend limited budgets. Well-organized volunteer projects accomplish substantial work with minimal financial investment.

Partnership Development: Collaborate with university archives, library digitization services, alumni association resources, or national organization programs providing technical assistance, equipment access, or financial support.

Technology Leverage: Cloud storage, free digitization apps, social media platforms, and other readily available technologies enable preservation activities impossible or expensive using traditional methods.

Integration with Existing Activities: Incorporate preservation into existing programs rather than creating separate initiatives. Add historical components to recruitment events, integrate preservation into new member education, or feature historical content in regular communications.

Leadership and Volunteer Turnover

Annual officer transitions create continuity challenges:

Documentation and Training: Comprehensive documentation of preservation systems, workflows, and responsibilities enables smooth transitions between successive historians and volunteers. Detailed training materials prevent knowledge loss.

Redundant Knowledge: Ensure multiple people understand preservation systems and protocols. When only one person possesses critical knowledge, their graduation creates crisis.

Alumni Advisors: Engage alumni volunteers providing continuity across student leadership transitions. Long-term alumni involvement creates institutional memory surviving annual turnover.

Sustainable Systems: Design preservation approaches requiring minimal specialized knowledge or time-intensive maintenance. Systems demanding exceptional expertise or constant attention fail when key individuals graduate or become unavailable.

Recognition and Succession: Identify and cultivate future preservation leaders before current volunteers complete their involvement, ensuring smooth transitions through overlap periods.

Technical Challenges and Obsolescence

Technology-dependent preservation creates specific vulnerabilities:

Standard Formats: Use widely adopted file formats and mainstream platforms rather than proprietary systems. Standardization reduces obsolescence risk and ensures accessibility if original software becomes unavailable.

Regular Migration: Plan periodic migration of digital materials to current formats and platforms. Proactive migration prevents technological obsolescence from rendering materials inaccessible.

Professional Support: For interactive displays or complex digital systems, work with vendors like Rocket Alumni Solutions providing ongoing technical support, regular updates, and migration assistance ensuring systems remain functional despite technological change.

Multiple Formats: Maintain high-resolution master files alongside web-optimized versions. Preservation copies protect against quality loss when web formats evolve.

External Backups: Don’t rely solely on organization-managed systems. Include third-party cloud backup services providing redundancy if organizational systems fail.

Privacy and Sensitivity Concerns

Historical materials sometimes contain information requiring careful handling:

Privacy Policies: Establish clear policies regarding what historical information is publicly accessible, what requires authentication, and what remains restricted. Balance historical access with legitimate privacy interests.

Sensitive Content: Historical materials sometimes contain dated language, problematic attitudes, or documentation of controversies requiring contextual explanation rather than deletion or unrestricted publication.

Living Individuals: Materials documenting currently living individuals raise different considerations than clearly historical records. Obtain appropriate permissions or implement access restrictions for recent materials.

FERPA Compliance: For university-affiliated organizations, understand federal education privacy regulations affecting what student information can be shared and implement appropriate protections.

Graduation Transitions: Establish timing policies for when current member information transitions into historical archives—typically after graduation creates natural transitions from active membership to alumni status.

Incomplete or Damaged Historical Collections

Many chapters discover their historical collections have significant gaps or damage:

Acceptance and Realism: Accept that perfect comprehensive collections are rarely achievable. Document and preserve what exists rather than becoming discouraged by gaps or imperfections.

Crowdsourcing Materials: Solicit historical materials from alumni, families of deceased members, and community members who may possess photographs, documents, or artifacts from your chapter’s history.

Oral Histories Filling Gaps: When documentary evidence is lacking, oral histories from knowledgeable alumni can partially reconstruct missing information while acknowledging these reconstructions are based on memory rather than contemporary documentation.

Triage and Prioritization: Focus resources on saving materials at greatest risk and highest value rather than attempting to address all problems simultaneously.

Professional Conservation: For severely damaged materials of exceptional significance, consult professional conservators rather than attempting amateur interventions potentially causing further harm.

Anticipated challenges with proactive strategies prevent preservation efforts from stalling when predictable obstacles emerge.

Conclusion: Your Organization’s Legacy Depends on Today’s Stewardship

Fraternity and sorority history represents irreplaceable heritage documenting student life, higher education evolution, women’s educational progress, leadership development, and community values across generations. This organizational heritage survives only through intentional preservation by current members and alumni who recognize that today’s stewardship determines what future generations inherit.

The preservation imperative extends beyond nostalgia. Well-maintained archives strengthen alumni engagement, support effective recruitment, facilitate networking, provide institutional memory during challenges, demonstrate organizational values, and position Greek organizations as responsible stewards of important historical traditions. Heritage conservation provides both retrospective protection and prospective benefits justifying preservation investments.

Technology has transformed what’s possible for historical preservation. Digital archives eliminate space constraints while providing universal accessibility. Interactive recognition systems transform static historical materials into engaging experiences. Cloud storage protects against catastrophic loss. Comprehensive platforms make sophisticated preservation practical for organizations of all sizes.

Yet technology merely enables preservation—it never replaces commitment to heritage conservation. Success requires understanding what materials have historical value, implementing appropriate preservation methods, creating accessible archives, documenting institutional memory, establishing sustainable systems, and engaging communities in ongoing stewardship.

For fraternities and sororities seeking to preserve their heritage effectively, comprehensive approaches combining physical conservation, digital preservation, interactive technology, and community engagement create sustainable preservation ecosystems serving organizations across generations.

Solutions like Rocket Alumni Solutions provide specialized platforms designed specifically for organizational recognition and historical preservation. Our systems combine intuitive content management, interactive touchscreen displays, web accessibility, search functionality, and ongoing support making comprehensive historical preservation practical and sustainable. From initial digitization through ongoing content management and system updates, we partner with Greek organizations protecting their unique heritage while making it accessible and engaging for current and future members.

Preserve Your Fraternity or Sorority History

Discover how modern digital recognition systems can help your Greek organization protect irreplaceable heritage while creating engaging experiences for members and alumni.

Rocket Alumni Solutions specializes in comprehensive historical preservation platforms featuring interactive displays, searchable archives, multimedia integration, and intuitive management tools designed specifically for fraternities and sororities.

Schedule a Preservation ConsultationThe organizations that will thrive in coming decades are those that honor their past while embracing their future—preserving heritage that grounds organizational identity while remaining relevant to contemporary members. Your chapter’s history is unique and irreplaceable. The preservation decisions you make today determine whether that history survives to inspire the next century of members or disappears into forgotten storage rooms and fading memories.

Begin your preservation journey today. Assess your historical collections, prioritize vulnerable materials, implement appropriate conservation methods, create digital archives, document oral histories, establish sustainable systems, and engage your community in heritage stewardship. Future generations of your fraternity or sorority will benefit from your commitment to preserving the remarkable story of your organization.

Whether implementing comprehensive digital systems, conducting targeted digitization projects, organizing volunteer preservation teams, or simply beginning systematic documentation of current activities, every preservation action protects organizational heritage and creates foundation for continued historical stewardship. Your chapter’s legacy depends on the preservation choices made today—make them count.